|

|

Hereditary surnames began to be adopted during early mediaeval times, and the family name Haas emerged from Bavaria. Chronicles first mention Ruediger Hase in Bavaria in 1173; Henrich Hase, the owner of the inn "zum Hase" in Basel in 1293; the name Hass appears in Prague in 1363.

The Haas surname would eventually emerge as a noble family with many influential branches, and become noted for its involvement in social, economic and political affairs. The Family Coat of Arms for most lines is a blue shield displaying a gold hare courant.

|

Within the Holy Roman Empire these territories gained a wide range of independence, but were under constant threat by the French, who sought, from the 17th century onwards, to incorporate all the territories on the western side of the river Rhine. This was obviously not a safe place to raise a family, so the Haas family had to move a lot.¹

Simon was probably born around 1661, in the winegrowing village of Albsheim an der Eis, is a district of the community of Ortsteil der Ortsgemeinde Obrigheim in the Palatinate (Pfalz) in the Rhineland-Palatinate (rheinland-pfälzischen) district (Landkreis) of Bad Dürkheim. Today the Bad Dürkheim district is located in the Palatinate between Ludwigshafen am Rhein in the east and Kaiserslautern in the west. The west of the district is part of the Palatinate Forest, and the east is part of the Upper Rhine Plain, the middle is part of the hilly landscape on the German Wine Route, which runs through the district from north to south over a length of a good 30 km.

|

Simon's parents were probably Hanß Nickel "the Elder" Haaß (1638-1676) and Anna Maria Flauth (1641-1684), who had possibly emigrated from Norway as itinerant laborers, and were married on 9 Nov 1675 in Rehborn, Bad Kreuznach, Rheinland-Pfalz. A man living in the this area 400 years ago was a commodity more than a person, and "freedom" as we know it today was unheard of—there wasn't even a word for it in the language. (Nothing comes for free in the mind of a Reformist Christian.)

The population in the area was split into two groups, labeled either Leibeigene ("serfs") or Leibfreie ("free subjects") with more rights than serfs, but still bound to their local ruler. Essentially, the best a man could hope for was that, through hard work and penance, he could eventually rise out of serfdom to earn the privilege of citizenship, which was called Bürgerrecht. With this, a man could gain property and possessions, which could in turn provide wealth and power, strengthen his family through political influence, and give him a say in property disputes. Bürgerrecht wasn't freedom, but at least it gave a man a voice in determining his fate.

In order to attain Bürgerrecht, a serf had to register as a taxpayer and provide church penance. There was no separation of church and state—so you had to worship under whatever faith your ruler commanded, and paid that church. The official state religion could change as often as the rulers—and in feudal Germany, they changed a lot! In Albsheim, the independant parish (formerly St. Stephan, a branch of the Lutheran Asselheim parish) was built in the 12th century in Romanesque style. It is the most important and oldest building in town, located in the northwestern area of the village, directly on the main road.

"The tallest Trees are most in the Power of the Winds, and Ambitious Men of the Blasts of Fortune."

—William Penn

|

Therefore, we can assume that Simon Haas had plenty of siblings, although few would have survived.

Then around 1677, when Simon was 15 or 16 and about to enter adulthood, he may have heard about William Penn, who was then touring the Rhine to promote a new land across the ocean, where you could decide for yourself what to believe and which religion to follow. Penn found a receptive audience in the area—and it's probably when Simon first heard of America.

Living in that sort of squalor also meant there wasn't much chance for Bürgerrecht.

"Justice is the insurance which we have on our lives and property. Obedience is the premium which we pay for it."

—William Penn

|

In 1684, Simon was documented at a Reformed Church event in 6791 Steinwenden, 16 km. west of Kaiserslautern (western Germany, today), at the edge of the Palatinate Forest. The French repeatedly invaded and occupied the area, residing in Kaiserslautern from 1686 to 1697. It was restored to be part of the Palatinate after the treaty of Utrecht, but the Haas family had moved on by then.

We see next Simon in Lutheran Churchbooks in 6791 Neunkirchen a/Potzbach, 6 km. further north (Neunkirchen is a Kreis, or district, in the middle of Saarland, between what are now the countries of France and Germany in the Holy Roman Empire. The town was situated on either bank of the Blies, a major tributary of the Saar River.

|

Adding to the misery, Simon became a young widower (an all-too common event in this area and time), when his wife Anna Maria passed away. Fortunately they were able to produce a son:

CHILDREN OF SIMON HAAS AND MARIA ELISABETHA UHL |

|

The Zöller family originated in Bavaria, Germany. The Family Coat of Arms is a red and silver shield displaying three pomegranates. As hereditary surnames were adopted in that area beginning in the 12th century, people were often identified by the kind of work they did. Zöller is an occupational name for a toll-taker or tax gatherer. The Zöller family became landed aristocrats and they resided in an elegant feudal manor on a vast estate in Bavaria. They branched into many houses in Austria and Switzerland, and their contributions were sought by many leaders in their quest for power. Chronicles first mention Eberhard Zollner of the town Eger on the border between Bavaria and Bohemia. Chronicles also mention Hartman der Zoller of Emmerdingen in 1392, and Johann Vryenstat der Czoellner of Liegnitz, Silesia in 1388. Anna Rosina's wing of the family in Mackenbach was obviously not as powerful, but her courage and resilience would bring Simon children who could prosper and thrive in a harsh new land. The children of Simon Haas and Anna Rosina were:

CHILDREN OF SIMON HAAS AND ANNA ROSINA ZÖLLER |

The Simon Haas family appear in a Lutheran Churchbook at Sippersfeld (17 km. northeast of Kaiserslautern) in 1702, and Rosina was a sponsor "from Etschberg at Neunkirchen," at a church event in 1706. But before things could get too peaceful, a French move to expand into the Empire started yet another war. Then came the 'War of the Grand Alliance' in which Louis XIV, who was claiming part of the Palatinate for France, fought the League of Augsburg—a coalition of European princes who refused to hand over their land. The conflict lasted eight years, from 1689-1687. What land that Louis didn't want, he destroyed. In fact, he even destroyed a lot of the land that he did want!

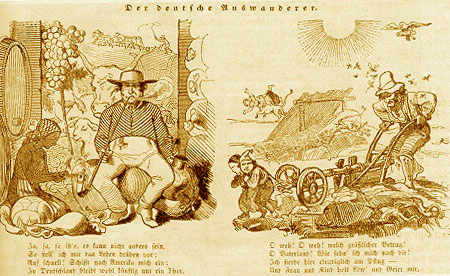

Finally, the Treaty of Ryswick restored the contested lands... but by that time the land had become so ravaged that many of the inhabitants fled the area entirely, some following William Penn and becoming the earliest German settlers of America—the Pennsylvania Dutch.

Those who stayed behind were then faced with the War of Spanish Succession, from 1702-1713, which completed the destruction of the area. The farmland became barren and charred, villages were destroyed, and the inhabitants were imprisoned, burned at the stake, broken on wheels or drowned. Simon knew that it was time to leave, and find a better future somewhere for his children.

|

|

|

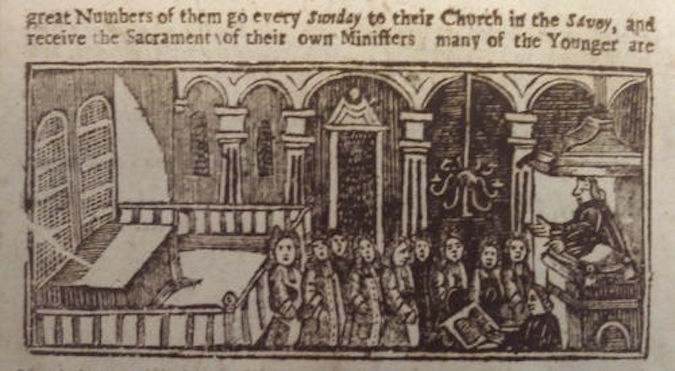

"They have endured one hundred years of war—King Gustavus Adolphus burned the city of Spiers in 1633. Invaded by Imperialists in 1644, by Germany in 1676 and by the Dauphin in 1688. Restored to the German Empire by the Treaty of Reswish, then destroyed by the French in 1693 who made a desert of 2,000 cities, towns and villages; destroying their vines with design to make so fatal a waste that the country might never be peopled or inhabited again. Vast numbers of Palatines perished in the woods and caves, among the wild beasts, through hunger, cold and nakedness."

—From a House of Commons investigation of the "Poor Palatines now living in London," as recorded in the "Ecclesiastical Records of the State of New York," Vol. 111

|

Queen Anne then agreed to send Kocherthal and a group of forty colonists to Carolina, not only funding their travels but also by supporting the colonists until they could get established. Kocherthal's report of this in an appendix to the third and fourth editions of his book caused a sensation in the region. The New World became more than an escape for these impoverished people—it became the Promised Land. Soon the rumor circulated that Queen Anne might be willing to support another group from along the Rhine. While Kocherthal had made no promises in his book, the possibility was there. And possibility was the best that someone living in poverty like Simon Haas could hope for.

During 1709, approximately 13,500 German and Swiss emigrants would apply for passage to the English colonies... and after seeing all of the death and destruction in his country, it sure must have sounded good to Simon.

|

|

Kocherthal had persuaded Queen Anne that Palatine labor would be a valuable asset in establishing and fortifying her colonies, so the Board of Trade suggested that the new load of Poor Palatine refugees should be settled in Antigua. But upon the opinion that these cold weather Europeans would not be suited to working in the hot climate of the West Indies, it was then suggested that they be directed to the Hudson River Valley in the Province of New York, instead. (After all, Indian attacks and below-zero winter temperatures were much more enjoyable than drinking rum and coconut milk on a sunny beach, right?) The Germans would be used on the frontier, as a buffer against the French and the Indians. (In other words, the Palatines would be stationed on the land that would be attacked first, giving the British time to prepare. It was also hoped that through Palatine trade and intermarriage with the Native Americans that France would lose the support of the Indian Nations.)

The British decided to send some 3,000 refugees to America, from the Palatinate, Franconia, the Archbishoprics of Mayence and Trèves, and the districts of Hessen-Darmstädt, Hanau, Nassau, Alsace, Baden, Würtemberg and Zweibrücken. Although the name "Palatine" would be used indiscriminately by the British to describe all of the travelers collectively, they were actually from hundreds of different provinces in the region, with numerous local governments, religions, and the various nationalities (many were migrants who had relocated in these regions unsuccessfully). Collectively they were called Teutschen (the equivalent of "Germans" today).

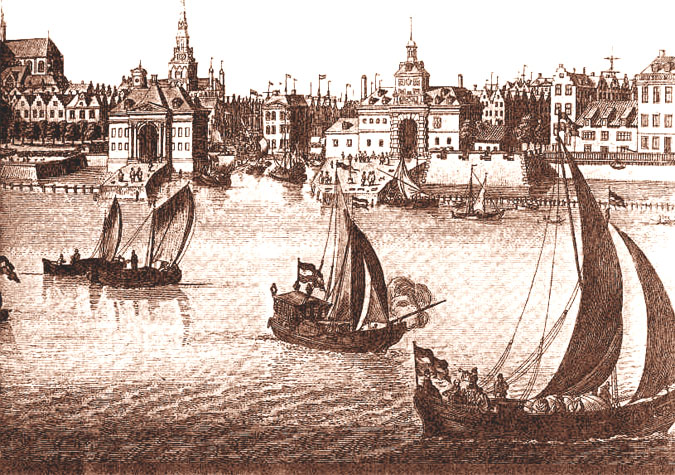

Simon made the cut to emigrate with the British, and in the spring or early summer of 1709, his family was in a group that left for Rotterdam, the first stop on their journey. They traveled by riverboat on the Rhine River, and then made their way to Holland. The mood was hopeful, even jubilant, and they sang hymns all the way to Rotterdam, leaving their homelands behind. There would be new opportunities in the Colonies... and most importantly, there would be land: Fresh, unspoiled land where Simon and his children—and their children—could finally prosper. He wanted that milk and honey. True Bürgerrecht.²

But it would be many months before the Haas family would arrive at this land of opportunity with the "Wonder Fleet." Along the way he would face poverty, starvation, disease, and death—and would find that there wasn't any "milk and honey" waiting for him, either.

|

"Let these good pious Palat'nates, And all such strange we know-not-whats, In their wise interloping Freak, Go to the Devil's Arse a-Peak."

—From the English poem, "Canary-Birds Naturaliz'd in Utopia," published in 1709.

The Palatines arrived at Rotterdam in 1709, but then there was another delay in the journey. So the stranded families lived for many weeks in what can best be described as a shanty town—although that might be glamorizing it too much. It was really just a bunch of primitive shacks covered with reeds. The Palatines were questing after "milk and honey"—but now they were having trouble even finding water and bread! Finally, the Mayor of Rotterdam took pity on them and donated some food and supplies.

Still, as bad as the conditions were at Rotterdam, the journey to London was even worse. It was supposed to have been a voyage of under four weeks, but they didn't actually arrive in London until months later. Furthermore, if they thought the British would be prepared any better than their hosts at Rotterdam, they were in for another in what would become a long line of disappointments.

The arduous journey was already affecting the emigrants. Many were sick, most were hungry, and they all were scared, trying to find temporary shelter in a strange land where everyone spoke a different language.

|

"What freak brought these poor creatures hither is not easy to guess ... Upon whose motive they were encouraged to come hither and what they are to do now they are here, is out of my reach."

—Roger Kenyon, after visiting the Palatines at the Blackheath Camp, August 1709.

|

What Kocherthal found in London was that the British people, convinced they were going to lose food and jobs to these new arrivals, hadn't done much to welcome the "Poor Palatines"—in fact they had rioted, and many attacked any German-speaking immigrants. Each day had grown worse, and many of the refugees were giving up, accepting offers to go to Ireland and work as share croppers. Others were returning to what was left of their homelands. But not Simon Haas. He had persevered. He could hardly picture life getting any worse... But it would.

Finally, around Christmas time in 1709, some 845 families boarded eleven ships for the long trip across the Atlantic Ocean... Where they continued to wait for a go-ahead from the queen. So Christmas was spent on a smelly, overcrowded boat.

Christmas wasn't celebrated much in England at that time, anyway. It was meant to be a day of penance and contemplation. The Germans, however, loved celebrating the holiday, and so there were probably some games and activities on the ship, despite their desperate situation. The children could have expected a visit from Pelznickel (Saint Nicholas in furs), better known as "Belsnickel." This version of Santa liked to scare children half to death, before changing character and giving them sweets. Of course, with no money, fruit or candy (let alone a barn), and with the anticipation of a long, dangerous trip across the Atlantic, the celebration was probably subdued.

The Haas family waited to discover their fate from the British authorities, but an answer wasn't forthcoming. The Palatines remained onboard their docked ships for several more months before actually sailing—just waiting, starving and grieving.

The ships continued to sit for a total of six long months in the Thames. Finally, in April of 1710, the convoy set off for the New York Colony.

"When they are buried all the attendants go singing after the corpse and when they come to the grave, the coffin is opened for all to see the body after it is laid in the ground they sing again for some time and then depart. They carry grown people upon a bier and children upon their heads."

—Daniel Defoe: A brief history of the poor Palatine refugees, 1709

|

|

|

Seeing the wretched state of the starving, sickly, disease-infested passengers onboard the ships (not to mention 500 rotting bodies awaiting burial), the New York City Council quarantined all of them offshore on Nutten (now Governor's) Island for almost four months without food and supplies. Obviously, this did nothing to improve their health, and 250 more perished from the fever, which was to be known for many years in New York City as "Palatine Fever."

|

So the Haas family faced another hard journey, this time on roads that were little more than footpaths cut through a forest of dense pine forest, to get to the barren wasteland where they were to live. They pulled small hand carts and wagons, and carried all of the food and supplies they could scrounge up on their backs (minus weapons and tools, which the British confiscated, to keep them from running off or revolting).

By October, these poor, weary immigrants were clearing the land and building small huts for shelter. But it was hard to build houses without proper tools: Some lived in caves that were dug into hillsides, with brush covering the entrance. Others lived in mud huts or cabins made out of very rough logs. The more capable built a cabin out of wood and stone, held together by clay and/or mud mixed with chopped straw (and if the land offered to the Palatines had anything in abundance, it was rocks) to create shelter from the fast-approaching winter. Most homes had only one room, which had a central stove or fireplace for cooking and keeping warm. A wooden bench was placed nearby so the family could sit and keep warm during the intense winter months, and that fire was kept burning all the time.

"(The men would) dig a square pit in the ground, cellar fashion, six or seven feet deep, as long and broad as they think proper.; case the earth all round the wall with timber, which they line with the bark of trees or something else to prevent the caving-in of the earth; floor this cellar with plank, and wainscot it overhead for a ceiling; raise a roof of spars clear up, and cover the spars with bark or green sods so that they can live dry and warm in these houses with their entire families for two, three or four years, it being understood that partitions are run through these cellars, which are adapted to the size of the family."

—Cornelis Van Tienhoven, secretary of New Netherland, describing the "dug-outs" in which the Palatines lived, in an official report sent to the Hague.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

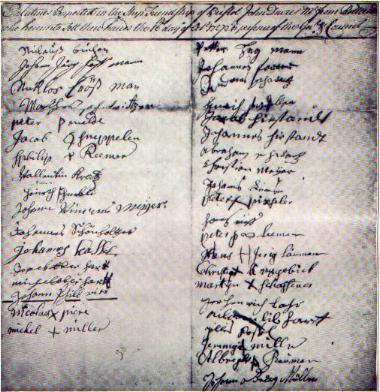

According to a manuscript in the Public Record Office in London, Simon Haas was listed as one of 847 debtors to the British Government for subsistence given them in New York City or in Hudson River settlements after their arrival there between 1710 and September 1712. Simon Haas made his first appearance on the Hunter lists on 4 July 1710 with 2 persons over 10 years of age and 1 person under 10; the size of the household increased to 2 persons under 10 on 31 Dec 1710, with the birth of a child. So when spring arrived, the Haas family began the long process of repaying their debt to the British: They were "redemptioners," or indentured servants, and had to work for a period of four to seven years to pay off the cost of their ocean voyage and relocation before they could earn their Freiheiten (rights as citizens—sort of a combination of Bürgerrecht and 'freedom'). The conditions were harsh; for instance, if an indentured child died before the contract was completed, the child's parents or siblings might be forced to work the remaining years of that contract, in addition to their own. Indentured servitude, unlike slavery, was entered into voluntarily—but you wouldn't know that by reading colonial newspapers, which were filled with advertisements offering rewards for redemptioners who had run away from their masters. Still, the Palatines could earn their way out of servitude—after which they were promised 40 acres each in "the land of Scorie"—rich Indian land had at one time been considered for settlement by Gov. Hunter. To Simon Haas; it must have literally been the promised land. But until that day, he was to live in "Wormsdorff," one of seven Palatine camps stationed along the Mohawk River.

The settlers at West Camp were pretty much left to themselves and allowed to build homes and to develop their farms. However, in East Camp the plan was for Simon Haas and the other settlers to make tar. Governor Hunter was under orders from Queen Anne was to build a Naval Stores facility. The British Navy was in dire need of pitch and tar for its fleet. The forest wilderness of pine trees in New York contained enough raw materials to supply the British Navy for many years. So he and the other redemptioners were put to work girdling pine trees for turpentine, in exchange for rations of food and drink. Unfortunately, the land picked for the project—"barren rocks" purchased by Hunter from Livingston, was completely unfit for the task.

Simon and the others collected what little tar and turpentine they could wring from the trees, which were unhealthy and rooted weakly into the sand. They would then report to Fort Hunter at the confluence of Schoharie Creek and the Mohawk River, where in exchange they were given the "queen's bounty"—meager rations of salted meat, bread and watery beer. (Not unlike my own diet in 2018.)

The Pitch and Tar project was a disaster. Tar was usually made at that time from the pitch of the Southern Georgian Pine. The northern or White Pine contains little pitch from which to make tar. Beyond that, the Palatines were as ill-suited for the work as the rocky land. They were raised to cultivate nature's bounty in farms and wineries—not destroy it for profit. Governor Hunter was soon forced to dip into his own money to keep the experiment afloat, and then looked to cost-cutting measures. He instructed the overseers to only distribute beer to the working men, and not their families (a great insult to the Palatines' customs). Then he started plans to put all of the new widows and orphans to work and "be no longer a burden." He actually started binding the children out to local farmers, effectively destroying many Palatine households—because there proved to be no differentiation between orphans and the children of poor parents. Simon's children were about the only possessions he still had. His family, as recorded on Governor Hunter's subsistence lists:

|

Simon and his family were pawns in that effort, just as exploited as the Indians, but with even fewer rights (at least the Indians were allowed to leave the Fort).

After crossing the Atlantic, surviving disease, cold, and angry Indians, Simon and Co. were still poor, still cold, still in danger, still slaving under a foreign ruler—and now on top of everything else, heavily in debt. They wouldn't be allowed leave the compound until all of their travel debts to the British government were repaid. But there was a reward for all of this: Simon's forty acres in the land of Scorie—land to settle and build on, that his sons could develop—and then their sons, too. Simon and Anna Rosina had at least three children, as well. Women married during indentured servitude were supposed to be bound to celibacy for five to seven years, but Anna Rosina had children right away:

CHILDREN OF SIMON HAAS AND ANNA ROSINA ZÖLLER |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Finally, in late 1711, the Whig party lost control of the British Government to the Tories, so support for Gov. Hunter declined, and, incredibly... the situation grew even worse! The entire "Pich and Tarr" project was shelved. Without Hunter's continued "financial support," the Palatines were soon left to their own devises... of which they had none. They weren't allowed to own farming tools, guns, or anything that would've allowed them to fend for themselves.

As for the promised land—the Schoharie Valley, there was worse news: Jean Cast, Governor Hunter's assistant commissary agent (meaning he was the guy who passed out the tools, rations and the rags to wear), informed the Palatines that the "Scorie" land would only be given to them after they had worked off the cost of their transportation to New York, after the charges for their food and drink had been cleared, after Livingston had earned a profit, and cruelest of all, after the cost of the coffins for the ships' dead had been discharged. The Palatines felt they had paid more than enough for their forty acres, so they began to plot an alternate plan...

The Mohawk River at Stone Arabia, as it looks today. |

"We came to America to establish our families—to secure lands for our children on which they will be able to support themselves after we die."

—Palatine refugees to their overseers in "Documentary History of the State of New York" (Albany, 1849-51)

|

While slogging through deep snow and dense forest in freezing temperatures, and running from the "law," it must have seemed to Simon Haas that life hadn't changed a bit for him since leaving Solms-Hohensolms.

For two weeks the desperate escapees cleared a path west of Albany "with the utmost toyle and labour," through the wilderness of the Helderbergs, down Fox's Creek... to a small brook where they stopped for "a general purifying"—cleansing themselves of all the grime and bugs they had accumulated on the journey (the brook is still known today as "Louse Kill" in honor of the event).

They were given food and shelter by friendly Mohawk Indians, and bartered for their land (which, as usual in those times, involved liquor)...Who knows, maybe the Indians sympathized, because they had been screwed over by the British, too. Many influential figures among Indians and whites crossed over from one cultural sphere to another, speaking various European and Indian languages and intermarrying, and forming political alliances between the two rapidly merging worlds. In New England some Indians still lived in traditional wigwams, but they filled them with European-manufactured furniture and decorative items. Some members of the Oneida tribe of the Iroquois confederacy practiced Presbyterianism, although simultaneously retaining traditional beliefs and rituals. Some Indians adopted European dress but retained the loincloths and nose rings of their own cultures.

|

If Hunter wasn't already angry that his redemptioners had bolted from his fort and left him 20,000 Pounds in debt from the failed "Pitch and Tarr" project, now they were squatting on his most profitable land! "Being arrived and almost settled, they received orders from the Governor not to goe upon the land, and he who did so should be declared a Rebel."

Clear title or not, Simon Haas cleared the land for a farm on the land he was promised. Having been forced to leave behind what few tools he had, he made do with whatever he could make from the forest... and on several occasions he and the other pioneers forcibly ejected land agents, including Governor Hunter's sheriff, as later reported by John M. Brown: "But when the Sheriff began to meddle with the first man, a mob of women rose, of which Magdalene Zee was captain. He was knocked down and dragged through every mud pool In the street; then hung on a rail and carried four miles, thrown down on a bridge, where the captain took a stake out of the fence and struck him in the side, that she broke two of his ribs and lost one eye; then she p*ssed in his face, let him lie and went off."

So the relations between the Palatine rebels and their former overseers deteriorated even further. Some had prices on their heads, and all the men avoided going into town for supplies, fearing arrest by the British.

Palatines believed that property didn't belong so much to an individual as to families and clans. While individually held, property and liberty were defended by the community. Land was acquired, fought for, settled, and eventually divided among the children with each successive generation—when there was no more land to divide, they moved west toward open country. And with no legal land available, Simon's children began to move on to other counties, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania.

"Simon Hass" was recorded with his wife and children was at Wormsdorff in the East Camp (now Germantown, New York) in Livingston Manor, ca. 1716/17 (Simmendinger Register). The Palatines on the frontier adopted Indian ways in the form of clothing, canoes, and native foods. They grew Indian corn and hunted just as Native Americans did. They soon created and wore breechcloths and leggings and were quite proud of their ability to hunt and live off the land like Indians.

Wherever Simon's farm was, it had to be self-sustaining, as carpentry work wasn't very lucrative, seeing as his clients had no money. Fortunately, the British had been wise in their choice of destination for the Palatines: Eastern North America is quite similar to the Rhineland, and therefore an ideal fit for the Germanic farmer: The soil and climate are similar, and the land almost identical—prime flat farmlands cover the Hudson river, just like the Rhine, with the same kinds of maples, oaks, beeches, and ashes in the low hills. So the Palatines didn't feel out of place, and knew how to create a farm.

Everything on the Haas farm had to be made or bartered. So, to create a self-sustaining enterprise, on top of the pastures and grazing land that Simon reserved for the livestock (providing meat, milk, dairy products, and leather), he built pens to raise chickens, geese and ducks for eggs, meat, and feathers (for bedding).

Surplus fats from the animals were used to make candles and soap. Shad and herring were caught making their runs up Schoharie Creek to the river, then pickled or smoked for later use. Wild pigeons were shot by the hundreds and preserved by pickling and smoking, as well.

To round out the diet, the Haas family probably grew wheat, corn, rye, and potatoes in his fields. Turnips, beets, cabbages, onions, pumpkins and peas filled the garden, with an herb garden as well, to grow Anna's food seasonings and "simples"—herbs used as medicine. She and the daughters would have picked berries growing wild in the forest. Tobacco would also have been grown for smoking, which almost all of the Palatine men and women enjoyed. Maple sap and honey were used as sweeteners. Hops were used to brew beer, which in most homes was more popular than water.

Tools were all homemade and crude—metal plows were not available, so Simon tilled the earth with a tree crotch shod with iron. Leather hides for tools were cured in the farm tanning vat.

Everything was stored in the barn, which had to hold enough autumn crops and salted meat to last through the long, brutal winters. In fact, the stone barns were usually better-constructed and more valuable than the log houses, for the simple reason that you could survive in a barn without a house, but not in a house with no barn to supply the necessities of life.

As for furniture, there was plenty of wood—maple, cherry, and (of course) pine—which was also needed to heat the house in the fireplace and stove.

Times were obviously rough, but you can't help thinking how cozy the nights must have been with Anna Catharina cooking a late dinner, with the kids nestled around the fireplace and Simon smoking his pipe and telling stories of the Old Country.

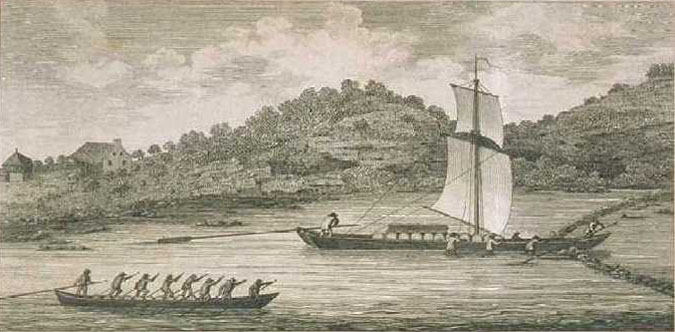

"A View of the Boats & manner of navigating on the Mohawk River." (Engraving by Christian Schultz.) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Then in 1715, it was enacted “That all persons of foreign birth professing Christianity could be naturalized by taking the oath of supremacy and subscribing the test and repeating the oath of abjuration. And Simon, now free of indentured servitude, did just that. On the 27th of April, 1716, Simon was Naturalized as a citizen of the British Empire, as "Symon Hawse" of Albany County (Alb. CCM 6:123). Sadly, the act was not to be construed to set at liberty any bondman or slave.

You may wonder why, after everything the British had done to Simon Haas, that he would have wanted to become a Naturalized citizen. The main reason was to protect the family land. England divided the people who dwelt within her borders into three classes—natural-born subjects, aliens, and denizens. But thanks to a British act passed in 1700, His Naturalized status enabled him to hold lands as well as transmit property to his children. This placed his children in the colonies on a par with subjects living in England itself.

Of course, there was another reason, too: "Liberty." Mind you, Palatines of the Reformed Church defined "liberty" in a very different way than we do today. Freedom was a deeply personal matter. It meant that they could make decisions for themselves without Hunter or Livingston breathing down your neck, but with a willing and unbending obedience to the government protecting them. Although Simon Haas had deep disagreements with the British, he still became citizen under the Crown, in opposition to the French government that had pillaged and destroyed their homeland. After six years of traveling without a home or flag, then working as a virtual slave, he could now at least say he belonged somewhere, whether he liked the local government or not, and could finally get some Bürgerrecht. Simon Haas was finally a free man! Syms P'r Hees was a Palatine Debtor in 1726 (Livingston Debt Lists)

Then in 1722, after many years of litigation, Gov. Hunter's successor, Gov. William Burnett, decided on a new strategy with the Palatines squatting in Scorie: He purchased new land in the Mohawk Valley for them to settle on legally. In 1723, 100 heads of families from the work camps were settled on 100 acres each in the Burnetsfield Patent midway in the Mohawk River Valley, just west of Little Falls. They were the first Europeans to be allowed to buy land that far west in the valley. He informed Britain that he would allow about sixty families that had been the strongest supporters of the crown to buy land at a decent price. Among them was the Haas family.

|

CHILDREN OF JOHANNES HAAS AND SARAH WILKENSEN |

|

|

|

|

NOTES ON THIS PAGE:

¹—It was not the king of France but the armies of the French Revolution who terminated the independence of the states in the region of the Saarland. After 1792 they conquered the region and made it part of the French Republic. While a strip in the west belonged to the Département Moselle, the centre in 1798 became part of the Département de Sarre, and the east became part of the Département du Mont-Tonnerre. After the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, the region was divided again. Most of it became part of the Prussian Rhine Province. Another part in the east, corresponding to the present Saarpfalz district, was allocated to the Kingdom of Bavaria. A small part in the northeast was ruled by the Duke of Oldenburg. On 31 July 1870, the French Emperor Napoleon III ordered an invasion across the River Saar to seize Saarbrücken. The first shots of the Franco-Prussian War 1870/71 were fired on the heights of Spichern, south of Saarbrücken. The Saar region became part of the German Empire which came into existence on 18 January 1871, during the course of this war.

²—Later generations would claim that our family and the other refugees wanted to leave their homeland for religious reasons, but this doesn't seem to be the case. The emigrants who left for England seemed to be evenly distributed in terms of religion (four lists of the 6500 "Palatines" arriving in London during 1709—comprising 1770 families—reveal 550 Lutheran families, 693 Reformed, 512 Catholic, 12 Baptist, and three Mennonite), so discrimination against any particular denomination seems unlikely. For the most part, they didn't seem all that religious, anyway. Antone Wilhelm Böhme, pastor of the German Court Chapel of St. James, related that only a few of the arriving Germanic immigrants in England came with a prayer book or similar religious work. Fewer still had a New Testament or Bible, until Queen Anne had them supplied in England. Simon Haas had much more earthbound reasons to leave for the English Colonies.

³—"The Embarkation Lists from Holland." In Early Eighteenth Century Palatine Emigration, by Walter Allen Knittle. Philadelphia: Dorrance & Co., 1937, pp. 248-274. Reprinted by Genealogical Publishing Co., Baltimore, 1965. Repr. 1982: "Name: Johann Haus; Year: 1709. Place: England or America. Family Members: 3 children. Page: 272; Johann Adam Haus, Year: 1709. Place: New York (p. 255). This man is either listed as "Hoff" or "Hussmann" on the Hunter Subsistence Lists in 1710 and 1712. In Palatine Families of New York, Hank Jones lists the last name as "Haas," and his family has a different point of origin. Records also show Hanss Henrich Zöller and a Johannes Zöller joining the 1709 migration to New York, but their connection to Anna Rosina is unknown.

⁴—Anglo-Norman names are characterized by a multitude of spelling variations. When the Normans became the ruling people of England in the 11th century, they introduced a new language into a society where the main languages of Old and later Middle English had no definite spelling rules. These languages were more often spoken than written, so they blended freely with one another. Contributing to this mixing of tongues was the fact that medieval scribes spelled words according to sound, ensuring that a person's name would appear differently in nearly every document in which it was recorded. The name has been spelled Wilkinson, Wilkisson, Wilkiesson and others.

⁵—According to genealogists Kirk Moulton and Dan Kinsey, working on the Secord and Simon Haas families, Johannes married Sarah Wilkensen (b. 1720) in the 1740s and believe that my line of the Hause family descends from this man... but no direct male descendants have been found to compare my Y-DNA with, so it is still unproven. "Simon" is a name that was often used for sons in my line (but this point is moot, because there are other names such as "Nicholas," "Zacharias," and "Bernard," that don't appear at all), and the John Hause legend from a family Bible states that he married Sarah, "a woman of fine English blood." If "Wilkensen" is actually "Wilkinson," that would be English. So hey, I'm open...

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

LITERARY SOURCES THIS PAGE:

¹—First generation. The European roots of the Simon Haas family were at 6791 Steinwenden (16 km. w. of Kaiserslautern; Chbks. begin 1684, Ref.), 6791 Neunkirchen a/Potzbach (6 km. furthern. ; Chbks. begin 1695, Luth.) and 6751 Sippersfeld (17 km. n.e. of Kaiserslautern; Chbks. begin 1702, Luth.). Hans Simon Haß, widower from Albsheim auf der Eys, Linniger (?) Westerb. Herrschaft, md. 15 Aug 1697 Anna Rosina - d/o Franz Zöller from Makenbach (Mackenbach), both Luth. (Steinwenden Chbk.). Rosina was a sp. from Etschberg at Neunkirchen, 1706. Simon Haas made his first appearance on the Hunter lists 4 July 1710 with 2 pers. over 10 yrs. of age and 1 pers. under 10; the size of the household increased to 2 pers. over 10 yrs. and 2 under 10 on 31 Dec 1710. Symon Haes was in Capt. Van Alstyn's Co. at Albany in 1715 (Report of the State Historian, Vol. I, p. 464). Symon Hawse was nat. 27 April 1716 (Albany Nats.). Simon Hass with wife and ch. was at Wormsdorff ca. 1716/17 (Simmendinger Register). Syms P'r Hees was a Palatine Debtor in 1726 (Livingston Debt Lists). The ch. of Simon¹ Haas and Anna Rosina were: 1) "A Child"², bpt. 20 Sept. 1705 - sp.: Philip Dil here, Margaretha Catharina - Theobald's ..., and Anna - w/o Baltes from Mackenbach (Neunkirchen a/Potzbach Chbk.). 2) Johann Nicolaus², born at Breunigweiler and bpt. 25 April 1707; mother not named in this entry (Sippersfeld Chbk.). 3) Anna Barbara², bpt. 10 June 1711 in the upper German colonies - sp.: Anna Berbel Simon Haase was conf. Dom. Quasim: 1726 at Loonenburg (N.Y. City Luth. Chbk.). 4) Zacharias², b. 12 Dec 1713 - sp.: Zacharias Flegler and wife Eve Anna Elisabetha (West Camp Luth. Chbk.). Zacrias Haas was enrolled in Capt. Jeremiah Hogeboom's Co. in 1767 (Report of the State Historian, Vol. II, p. 864). He md. 28 Sept 1737 Geesje Witbeek (Albany Ref. Chbk.) and had: i) Simon³, bpt. 18 Jun 1738 - sp.: Thomas Vlyd and Antje Vlydt (Albany Ref. Chbk.). Seyma Haas was in Capt. Fraens Claevw Jr.'s Co. in 1767 in Kinderhoeck (Report of the State Historian, Vol. II, p. 868). He md. Jannet Kohl and had issue at Germantown Ref., Linlithgo Ref. Kinderhook Ref., and Claverack Ref. Churches. ii) Lena³, bpt. 31 Aug 1740 - sp.: Johannes and Jannetje Goewyck (Albany Ref. Chbk.). iii) Anna³, bpt. 1 Aug 1742 - sp.: Lambert Kool and Willemtje Bradt (Albany Ref. Chbk.). iv) Anna³, bpt. 21 Oct 1744 - sp.: Anthony and Willempje Brat (Albany Ref. Chbk.). v) Catharina³, bpt. 23 Aug 1747 - sp.: Daniel and Alida Marrh (Albany Ref. Chbk.). vi) Johannes³, bpt. 6 Aug 1758 - sp.: Andries Witbeek and Maria Herder (Claverack Ref. Chbk.).vii) Anna³, bpt. 12 Aug 1761 - sp.: Jan de la Mettre and wife Heyltje Muller (Claverack Ref. Chbk.). This couple probably had other ch. 1748-57 (HJ). 5) Johannes², b. or bpt. 5 Aug 1716 at Nootenhoeck, Albany; bpt. at Klinckenberg - sp.: Justus Falckner the Pastor and Anna Catharina Stubber (N.Y. City Luth. Chbk.). 6) Anna Catharina², b. 2 Dec 1718 at Nootenhoeck and bpt. at Lonenburg - sp.: Jan Jurgen Rau and wife Anna Catharina (N.Y. City Luth. Chbk.). |

SOURCES FOR THIS PAGE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|