|

"I

would have hanged my own brother if he took part with our enemy in this contest."

—John

Adams

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

But our family wasn't alone: Benjamin Franklin's own son, William (then the governor of New Jersey, mentioned in the previous chapter), remained loyal to the British—even after torture and imprisonment by the rebels, who were led by dear old dad.

John Adams (later a United States President) estimated that a full third of the population were Loyalists (or 'Tories'), another third were revolutionaries ('Whigs'), and the final third were on the fence. Furthermore, he declared that a proper history of the conflict would never be told, because over 100,000 Loyalists who were not killed in the war were driven out of the United States, and exiled in England and Canada. Therefore, the story would only be told through the eyes of the victors.

At first, the Colonists appeared to have little chance to win. They possessed no trained armed forces, no established central government, no financial reserves and no industry to supply their effort. North America had been settled to export raw materials to England's factories, not create finished goods for themselves. So there were no manufacturing facilities to produce arms and support a war.

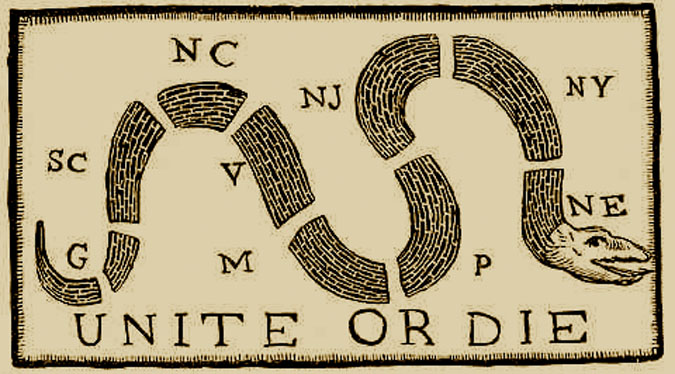

In fact, it was a miracle that the various Colonies could unify in the common purpose of a revolution at all. They were all separated by dense forests, rivers, and dangerous Indian land. Even when there were common borders, they would feud over the boundary lines to the point of war, then not allow their roads to connect. Ideologically the various Colonial regions were separated by issues of slavery, race and religion. For instance, the Puritans of New England hated the Anglicans of the south. And all that those two groups could agree on was that they hated the Catholics, Quakers and Jews. The North and South had already divided on slavery: the southern colonies having built their economy on it, while the northern colonies had practically abolished it (in fact, one of the victims of the Boston Massacre, ground zero for the revolution, was Crispus Attucks, a freed slave).

But despite all of their differences, everybody in Colonial America could agree on one thing: they all hated taxes! The problem was, nobody could agree on the best way to combat their rising tariff woes. The rebels believed independence from Britain was the only answer. But the Tories only protested "taxation without representation," believing that if they were to be taxed by Britain, then they deserved a representative in Parliament. Britain, however, disagreed with both views. In the view of the British, the Colonies were not part of Britain—they were a possessions of Britain, existing solely for profit. And the King's rebuke of the Loyalists gave the rebels just enough of a majority to start a war.

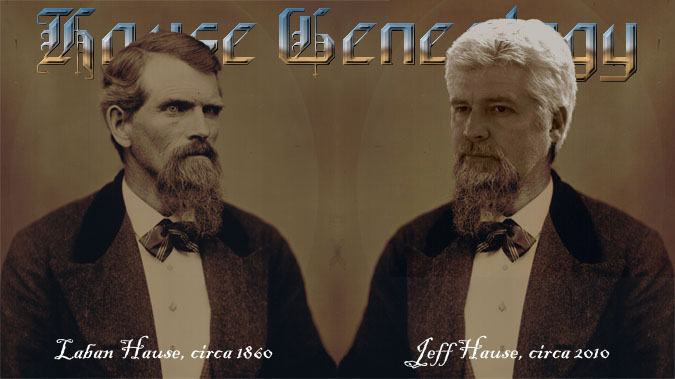

Technically, I'm descended from one of the victors, but I'll try to give the most unbiased account I can, in order to tell the story of the Haus family on both sides of the conflict.

Although it's just a family residence today, FORT HAUS or FORT HOUSE, the home of Captain Christian Haus,¹ was a stronghold for settlers against the French, the Indians, and the British on the western edge of St. Johnsville, Montgomery County, New York (one mile west of the town's center, and six miles west of Nelliston). Sometime in the mid-1800's it was modernized after the style of the day and the roof was flattened. It is located on Hillabrant Road, and can be easily seen from Route 5. This is a private home owned by Brandt and Marlene Rostohar and not open to visitors. |

|

At this time, the Tryon County Committee of Safety was formed in the Palatine District, where most of Johann's descendants were still located. This group would later be known as the Tryon County Militia and, still later, in the regular army, called the "Continental Line." These men would become the Colonies' primary line of defense on the frontier with Canada.

As hostilities escalated between Britain and the Colonies, a law of the United States Congress, passed on the 16th day of September, 1776, provided for the enlistment of 88 battalions of men to carry on the war for independence. During the war, the opposing sides took on the name of English Parliamentary parties. The "Whigs" were the patriot side and the "Tories" were the Loyalists.

In many ways, New York State was the principal battleground of the Revolutionary War. Approximately one-third of the skirmishes and engagements of the war were fought on New York soil. Revolutionary War records chronicle the descendants of Johann Christian Hauss enlisting over sixty times in the New York Militias alone during the conflict, some more than once. In fact, Johann's descendants made significant contributions to the war—on both sides.

|

|

So the legislature authorized that the remaining two regiments should be raised—but New York needed some way to induce more men to enlist. The Continental Congress promised that all officers and soldiers who remained in the service until discharged—or the representatives of those slain by the enemy—should be entitled to receive, upon the ratification of the treaty of peace, a grant of land in Ohio. So the Congress guaranteed every fighting man in the Revolution a bounty of 100 acres in the public domain (and officers in proportion to their rank).

Despite this, there were still not enough people enlisting in the New York army. People had no faith in government currency—for obvious reasons during a war to determine the government—but New York did have a vast surplus of land. So, it was decided to offer 500 more acres to the prior 100. Thus, the state decided to divide central New York into Townships of 100 lots, at 600 acres per lot. "The Military Tracts of Central New York" totaled about 1.75 million acres of bounty land and extended from Lake Ontario southward to the south end of Seneca Lake, and from the east line of Onondaga County westward to Seneca Lake. The present New York counties of Onondaga, Cortland, Cayuga, and Seneca were included, as were portions of Oswego, Schuyler, Tompkins, Yates and Wayne. Deeds in Central New York commonly refer to these "Military Tract Lots" as "Great Lots" or "Farm Lots." (Our Hause line would end up with one of these lots in Seneca County.) Here is a listing of Haus/Hause/House soldiers on the Patriot side, adapted from The House Family of the Mohawk:

TRYON COUNTY MILITIA |

||||||||||||

Second Regiment

Third Regiment

The Rangers

|

||||||||||||

THE LINE |

||||||||||||

Second Regiment

|

||||||||||||

THE LEVIES |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

COL. CLYDE'S REGIMENT |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

THE LINE |

||||||||||||

Fourth Regiment

Fifth Regiment

Green Mountain Boys

The Levies under Col. Weissenfol

The Levies

|

||||||||||||

ALBANY COUNTY MILITIA |

||||||||||||

Fourth Regiment

|

||||||||||||

DUTCHESS COUNTY MILITIA |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

ORANGE COUNTY MILITIA |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

ULSTER COUNTY MILITIA |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

COL. WYNKOOP'S REGIMENT |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

ALBANY COUNTY MILITIA |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

ALBANY COUNTY MILITIA |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

TRYON COUNTY MILITIA |

||||||||||||

Under Col. Stevens

Under Malcom

|

||||||||||||

ALBANY COUNTY MILITIA |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

ALBANY COUNTY MILITIA |

||||||||||||

|

A Loyalist is tarred, feathered and gagged with tea... all in the name of liberty and freedom of speech. |

The Haus family had its Loyalist side, as well. The descendants of Johann Christian Hauß had dispersed all over New York, Pennsylvania, and down south, and as their wasn't a uniform system of spelling, yet, variations on the name abounded (often on the same muster roll): "Haus," "Hawes," "Hauss," "Huus," "Huss," "Huff," "House," and, of course, "Hause" families would have members fighting in both armies—creating a rift that would eventually tear the family apart. Over in Schuyler County, Captain John Haus was a fierce Patriot who fought against... his own brother, Harmanus a Loyalist who rode with Butler's dreaded Rangers (as well as George Haus, who was either another brother or a cousin).

On September 15, 1777, a Loyalist named Major John Butler was issued orders to raise eight companies of "Royal Rangers" by the British army. They were to be the best of the backwoodsmen, "composed of men who understood Native American Indians, be accomplished woodsmen and have considerable endurance." They were uniformed in green coats, caps and dark-colored accouterments for concealment in the woods. Many added articles of Indian dress, such as moccasins and leggings.

"Butler's Rangers," were extremely active in the Mohawk Valley. Their principal duties were to work with loyal Indian allies in raids on the grain fields and frontier outposts of New York and Pennsylvania. Some companies ranged as far south as Kentucky and as far west as Michigan, battling with the likes of George Washington and Daniel Boone (who is descended from our ancestors in the Morgan family). They brought guerilla warfare to the conflict—something which regular British soldiers were untrained for. This made their battles among the bloodiest and nastiest of the war.

Harmanus Haus is the most infamous of the Mohawk Tories in our family. In fact, he became so notorious during the war that he appeared as the villain in a chapter of Jeptha R. Simms' classic book, The Frontiersmen of New York, in which he shot and scalped local Rebel hero John Bellinger:

"The

Frontiersmen of New York" | |

Christopher first discovered the foes approaching, and shouted the prophetic words of the times—"The Indians!" John Bellinger was an uncommonly strong and courageous man, and withal swift on foot. With uplifted fork he ran directly for the guns, quite as near to which was his Tory foe; his brother and Harter at the same time fleeing for the fort, pursued by the Indians. As John neared his own gun, House drew up to fire on him, but before doing so he called back his comrades by a signal whistle. He then fired, and one of freedom's boldest champions was weltering in his gore. Christopher and Philip reached the fort in safety. There were other Indians concealed near the field, as was afterwards understood, who dreaded the vengeance of John Bellinger more than that of a score of ordinary men. The enemy obtained; with his scalp and the plunder of his person, the three guns which the young men had taken to the field. The loss of this brave partisan was severely felt in the German Flats, for his was one of the master-spirits of that section, just suited to the times. But, like many noble young Americans, he was surprised and slain, either from envy or the British value to a Tory neighbor of his scalp-lock. House called back his accomplices to assist him, fearing if he fired and missed his victim, and their guns were unloaded, his fate would be sealed. He was well acquainted with Bellinger before the war. The remains of the fallen hero were taken to the fort and buried with becoming respect. Facts from Adam Rasback, corroborated by Frederick P. Bellinger, in 1845. |

|

He seems to have started his military career on April 1, 1760, in Dutchess County, as a 5'11", brown-haired 21 year-old from Tappan with a ruddy complexion, according to muster rolls. He joined Captain Jacobus Swartwout's (sic) company during King Phillip's War, when he battled the French and Indians alongside the British.³ Apparently he kept those Loyalist leanings and sided with the British during the Revolution, as well.

Now, to be fair, Harmanus' scalping story might have been written a lot differently if the Loyalists had prevailed, and his Canadian descendants are extremely proud to have him as an ancestor. By all accounts, Harmanus was a brave, talented frontiersman. According to The House Family of the Mohawk, he had been a family favorite before the war, and afterwards, Captain John Haus, the family hero on the Patriot side, always mentioned Harmanus "with regret." But Harmanus probably felt the same way about John!

After all, Loyalists were heavily persecuted during the war—they were tortured, tarred & feathered, stoned, and made to "ride the rails" (dragged without pants along a sharp steel blade) on a good day. And the reality is that they were just British subjects fighting an insurgency against their chosen government—protecting their homeland, as we all would—but they lost the war, and to the victors go the spoils, the land, the Simms historical books, and the Mel Gibson movie rights. Simms was also known to bend the facts for dramatic effect, and, after all, "Harmanus" is a great name for a villain. (You can't beat "harm+anus" as a compound word; his name was literally "beat your ass!") So who knows, maybe Simms just used the coolest-sounding villain's name on the list of Mohawk Loyalists.

|

And there were so many Hauses struggling to survive on those blood-drenched battlegrounds! We have now established Haus men on the Patriot and Loyalist sides in the war. But stranger yet, there were probably Hauses on a third front, too!

In 1775, George III of Great Britain, of German lineage himself, was desperately seeking to retain control of British North America, so he signed treaties with six German states to supply troops to defend the English interest in this part of the world: Hessen-Kassel provided the largest contingent of troops, so the German forces became known generically as "Hessians." Foremost in demand were the Jägers (Hunters). They were the European counterpart of the American riflemen. By 1781, there were 821 Jägers from Hesse-Kassel and 245 from Anspach in the British Army in New York.

At this time in the unending border wars in Germany, Großaltenstädten and Wetzlar, where many of the Hauß family still resided, had been swallowed up by Hessen-Kassel, which was now divided into districts, each of which was to furnish a given number of recruits to a certain regiment. So in one of life's cruel ironies, the Haus men probably faced more Hauses from Hessen, and the people who would've been their friends and neighbors just a few generations before!

Approximately 17,000 Hessian soldiers were sent to America, representing about 1 out of 4 able bodied men of military age of the population of that state, and they composed approximately one third of the British forces in the conflict—and most of the casualties, as well. How many of these Hessian casualties were in the Haus family is unknown, as the British rarely counted their German casualties. Others found new lives in the Colonies. For instance, a 34 year-old Johann Hauß from Gernsheim/Darmstadt was discharged from the British forces in 1783, and settled in Canada.⁴

The States of the Princes and Counts of Solm, with the Imperial Free Cities of Friedberg and Wetzlar (1797); Showing the region around Giessen, with parts of Hessen-Darmstadt, Hessen-Kassel and Hessen-Nassau identified. "Altenstetten" (or Großaltenstädten), the original home of Johann Christian Hauss, is located just above Wetzlar. (To see the entire map, click here.) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The first record of John comes as a private in General Herkimer's front guard in one of the most vicious battles of the war: The conflict at Oriskany, on August 6, 1777. Two years later, according to various book accounts and affidavits, he was taken prisoner by a war party of Indians and Tories, to whom he passed deliberately false information, preventing an attack on Fort Schuyler. Convinced that he was sincere, the Loyalists let him go after he took an oath of neutrality. (Page 269 of The Old New York Frontiers states: "From John House's further activities in the Revolution it would not seem that he took his oath of neutrality seriously.")

At least a half-dozen Haus men (and sometimes their families) were taken captive by the opposing side in the Mohawk area during the ensuing war, but they were almost always let go, because they had relatives in the other army who could vouch for them... But not always—records show that hundreds of New York farmers, women and children were tortured, killed and scalped during the war. How many of those were Hauses, both Loyalists and Patriots, is unknown. Mohawk Valley church records show that these men had once sponsored each other's children in baptisms, but now they were trying to kill each other. You've got to figure that Christmas dinner with the relatives at the Haus house was never the same again.

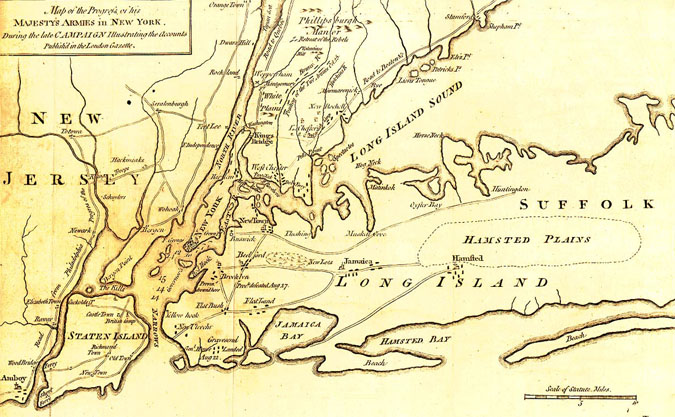

A British map of New York and the surrounding battleground. (To see the entire map, click here.) |

|

Meanwhile, Rebel General Nicholas Herkimer, hearing about St. Leger's invasion and the siege of Fort Schuyler, assembled approximately 800 militia troops from Tryon County and some Oneida Indian scouts to face them. He set out on August 4th from Fort Dayton (30 miles east of Fort Schuyler) to reinforce the fort troops and relieve the siege.

But Molly Brant, the common law Mohawk wife of local Loyalist leader Sir William Johnson and sister of Joseph Brant, sent word to St. Leger on August 5th that the relief force was only 10 to 12 miles away from Fort Schuyler. St. Leger dispatched a 1,200-man detachment of Mohawk Valley Tories and Indians under the command of Brant, John Butler's Rangers, and the Royal Greens to ambush the Rebel militia.

They chose an ambush point six miles east of Fort Schuyler, near the village of Oriskany. Dense virgin forest there provided excellent concealment for forces around a marshy ravine about fifty-feet wide, with steep sides, where an old military road descended to cross little Oriska Creek. Loose logs had been thrown across the mucky path to make it easier for wagons to cross. It was an ideal spot to attack, and the plan was to wait for the middle of Herkimer's straggling forces to be deep in the ravine, where the Tories and Rangers would attack. The Indians would then attack the flanks and rear, leaving no path for the rebels to escape. Herkimer's men would be cut to pieces in an open marshland. The Rangers, Indians and Royal Greens arrived hours in advance, removing all footprints, tracks and signs of their presence from the area, and waited...

Finally, around noon, General Herkimer and his men reached the ravine. He was waiting for a previously-agreed upon signal from the forces at Ft. Schuyler to advance—three cannon shots. But when the old general heard nothing and wanted to wait, he was goaded into pressing ahead by his overeager colonels: Cox, Paris, Klock, Campbell and Visscher, who accused him of being a Tory for delaying (Herkimer's brother was, in fact, fighting alongside St. Leger).

The Loyalist forces had covered their tracks well, and General Herkimer's Oneida scouts detected no enemy. So Herkimer gave in to his colonels, mounted his white horse and shouted, "Forward and follow me!" He then led the first 600 men into the trap. Fifteen supply wagons followed, and then the 200 soldiers of the rearguard. Then, as Herkimer completed crossing the ravine, the Mohawks and Rangers finally attacked. Their initial volley cut down most of the American leadership, including Herkimer, who sustained a serious leg wound, while his horse was killed.

What followed is detailed in an award-winning book:

"The Wilderness War: A Narrative" | |

|

Oriskany monument near Oriskany, New York, in Oneida County. Marker is on Memorial Drive near State Route 69 (New York Route 69). |

Both sides suffered heavy losses—mainly Indians on the Loyalist side—but about 500 of Herkimer's 800 men eventually died from the battle, and only about 150 escaped without serious injury. Nearly all of the Hauses survived, as they had probably banded together during the chaos. At least eight fought in the battle and only one that we know of (Conrad) was killed.

Hopefully Conrad died quickly, because many Americans were taken by the Indians, who favored a torture method of impaling the prisoners with turpentine-covered wood splinters, then setting fire to the splinters. Death took hours—followed by cannibalism, according to some accounts, which would not be inconsistent with Native American traditions of the time in that area. ("We're having the Hauses for supper! Yum!!!")

In 1884, a monument was erected to honor the soldiers. Its bronze plaques depict the battle and list the names of some of the participants, including Captain Christian Haus, Lieutenant Jost Haus, and Conrad Haus. The Hauses who fought on the other side aren't listed.⁵ (On a side note, in 2006 I found the actual Oriskany battle site: Beyond the official plaque commemorating the gruesome battle, it now holds a Burger King and a Dunkin' Donuts.)

Haus Women During the Revolution |

||

Elizabeth Scriber House told the Enterprise and News in 1931 about her great, great, grandmother, who lived near Fort Plain. She and her children escaped the burning of their village by Indians and retreated to the fort—only to find it nearly unoccupied, except for one old man and a 12-year-old boy. She and her neighbor donned soldiers' uniforms to masquerade as militia and make the fort appear manned. The Indians surrounded the fort and attacked. Then on command of the old man, the women fired. Several Indians fell, and the rest then retreated, never knowing that they were being held off by a total military force of one old man, two women and a few children. This story was recreated a few years after the press article in the novel, Drums Along the Mohawk, by author Walter "Walt" Dumaux Edmonds (July 15, 1903 Booneville, New York - January 24, 1998). The book, published in 1936, was a best seller for two years, taking a back seat only to ''Gone With the Wind.'' In 1939, it was made into a movie, directed by John Ford and starring Henry Fonda and Claudette Colbert. Another example: The family of Conrad House left Montgomery Co. sometime after 1768 and removed to Otsego County, one and a half miles east of Richland Springs. Their cabin stood on an Indian trail between Albany and Federal Corners. Then, during the Revolutionary War, Indians on the British side attacked the House cabin. Mrs. Engelge House escaped into the woods, but her 13-year old daughter was caught and carried off. After several years she reappeared with a child fathered by an Indian captor. This child was called Mary Manton. She became well-known in the area, and stayed visible until 1812, when she disappeared for good, presumably back with her Native American family. |

|

This was possible because the soldiers in the various Colonies had undergone a transformation during the course of the war. In fighting together against a common cause, they had stopped thinking of themselves as New Yorkers or Georgians or New Englanders: Fighting side-by-side, relying on each other, they had started to think of themselves collectively as Americans. That, more than any battle, signaled the birth of a new nation.⁶

But not all of the descendants of Johann Christian Hauß prospered in the new country. With the American victory also came the banishment of the Loyalists. In 1781 the newly formed State of New York began the confiscation of Loyalist land, and on July 15, 1783, the holdings of Harmanus and his cousin, George House of the Canajoharie District of Tryon County were confiscated and auctioned at a Sheriff's Sale. A later Claim by George to the British on August 30 said he joined them in 1777, served all the War under Col. Butler in the Rangers; Had some Lands on the Mohawk, had no Lease but had lived on them 15 years before the War, and had built a house. He only Claims for the Buildings 24£, he had 4 horses & 2 Colts, Utensils, furniture, grain in the ground, all of which he left behind. A day earlier (14 Jul 1783), John Jurry House of the Palatine District of Tryon County also lost all of his property. The Indians took some, the Rebels took the most.

| House, John Jurry—Farmer House, George—Yeoman House, Hermanus—Yeoman Also listed on the Military Roster: Daniel House, Frederick House, James House, John House, and Philip House. |

"Loyalist Landing," by Adam Sherriff Scott; United Empire Loyalists landing at the mouth of the Saint John River in May of 1783. |

With the war behind him, Harmanus was a model citizen in Canada, and still a great frontiersman: He served on the first Municipal Council of the Clinton Township and was named Poundkeeper and Town Warden in 1793—and as far as I can tell, he never scalped anybody that he caught!

He and Margaret had nine children altogether. Their daughter, Anna Margaret, married Joseph Smith on January 28, 1790, and their son, Harmanus Smith (named after his grandfather) later became a successful doctor and politician. His exploits were recounted in The Story of a Pioneer Doctor—Harmanus Smith by Vivian M. Spack, E.E.

So all in all, both sides of the Haus family, in the United States and Canada, were quite successful after the war. The century-old dream of Johann Christian Hauß, for his children's children to prosper, was coming true...

|

This closes my writings on the House genealogy for the present, hoping that further study will bring more interesting facts to light. In closing I want to thank those who have rendered assistance in procuring the information I have been able to give in these articles.

THE END (for Melvin Rhodes Shaver) |

But his dream lived on over the next 300 years through his sons, the sons of their sons, and on down to us, who have attained our Bürgerrecht and now are charged with ensuring that the humble dream of this poor, heroic man lives on even longer. That dream has survived wars, disasters, depressions, and debacles, even if our memory of Johann Christian Hauß himself has not. But through the hard work of the genealogists and historians listed on these pages, Johann Christian Hauß is being honored again—and we who have been given so much, thanks to him, should never forget. THE END (for me, but not for the Hauß family!) |

|

TOP PHOTO: Captain Christian House assists General Herkimer at the battle of Oriskany; This painting hung in the Officer's Mess of the USS Oriskany (CVA-34) while the ship was in commission (it's now on display at the Utica Public Library).

NOTES ON THIS PAGE

¹—History of Montgomery County, by Washington Frothingham, D. Mason & Co., 1892, p. 310: "Captain Christian House became prominent for his unremitting efforts in behalf of the American cause. His home at the time was near the west line of the present town, and his house was, as has been stated, converted into a fort and stockaded at his own expense and in a great measure by his own hands. For his many brave acts and faithful service during the revolution he never asked for compensation, and he lived to see the close of the war and victory for the cause he championed. He died soon after, however, and his remains were buried in an old cemetery, still in existence, near the former site of Fort House."²—"I have been researching an ancestor, Jonathan House, listed as belonging to the 'Mohawk' family, but I am not sure why. All I can find out about Jonathan is that he was probably born in 1748, lived in Shaftsbury VT in 1787, Sunderland VT in 1790, was a member of 'The Green Mountain Boys', moved to Onondaga NY, and died there in 1804. In House Family of the Mohawk, by Melvin Rhodes Shaver, Johnathan House is listed under 'Green Mountain Boys', Col. Ethan Allen, Commander. I have found elsewhere Jonathan documented as serving in Brownson's Militia, from Sunderland VT, fighting in Montreal in 1776 and the Battle of New York. He rode in the 'alarm at Cambridge' in 1781. In the 1787 census he lived in Sunderland, VT, the 1790 census he lived in Shaftsbury VT. The 1800 census has him in Onondaga, NY. Jonathan House was married to Mary Smith and had something like nine children. The only children I can confirm are Selimus, born in the mid 1780's, Seclendia, born in 1789 and my ancestor, Philoteus House born in 1801, in Onondaga. I think they were Baptists. I have not found anything that makes me think that Jonathan was German, other than that one reference, but who knows? My grandmother did some research in the late 1930's, that just says that Jonathan was probably born in Albany county in 1748. Thank you, Jeff, for assistance!"—Martha Burdick (e-mail)

³—New York Colonial Muster Rolls: 1664-1775: Report of the State Historian of the State of New York. Vol. II, Wynkoop, Hallenbeck Crawford Co., State Printers, New York and Albany, 1898. page 564: Harmanus House of Tappan in Swartwout's Co., 1760.

⁴—Brunswick deserter-immigrants of the American Revolution, by Clifford Neal Smith. Thomson, Ill. Distributed by Heritage House. 1973. Page 16.

⁵—HFOTM: "The name of Conrad House which is not listed in any of the foregoing companies has been placed upon the Oriskany Monument as well as that of Captain Christian House and Lt. Yost House. Nelson Greene in his "Story of Old Fort Plain" says Lt. John Joseph House was taken prisoner at the Battle of Oriskany.

"New York in the Revolution, supplement page 118 mentions aid given to family of John House, family of 4, dated March 28, 1780, signed Christopher P. Yates, supervisor of Palatine District, County of Tryon.

"'Public Paper of George Clinton' first governor of New York mentions among other prisoners taken near Fort Plank in Tryon county, Aug. 2, 1780.

"Belonging to widow of Henry House, Christina age 16, Elizabeth age 11 and Conrad age 7.

"Wife and children of Henyose House, Elizabeth 21, Christina 4, Jacobus 9 months. Also Elizabeth daughter of George House and Conrad son of Adam House. (Remember Harmonious was also referred to as Adam ~ J. H., 1998) Those prisoners were taken to Canada in March 1781 and on page 724-725 of Vol. 6 is an account of his demanding their return under threat of reprisal. "In the Story of Old Fort Plain" by Greene, Lt. John Joseph House of Minden killed.

"In Simms' Frontiersmen of New York Vol. 1 page 573-574 under tile of Fort Plank mention is made of Capt. Joseph House of military who was living with Plank and usually commanded the post in the absence of field officers. Facts from Lawrence Gross and Abraham House. The latter named was residing in 1846 on the old Plank farm, now owned (1882) by Adam Failing.

"On wall of the Van Rensselaer club, Canajoharie, N. Y. number of days that the officers and men of my company have been on duty since the 8th day of July last, 1780 to the 28th of May, 1781. Those names appear, Capt. Joseph House, Jost C. House, Pillerst Haus, Henrick Haus and Geo. Haus.

"We also have (a) copy of (a) letter from Pension department, Washington, D. C. giving war record of a Christian House (not Capt. Christian) who served with Capt. Jacob Singer's Reg. Capt. John Winn's, Capt, Robert McKean's, etc. which shows the number of enlistments some of the men made during the war. Would be glad of any data on any of the above mentioned that any of your readers may have. Also any comments or corrections would be welcomed."—M.R. Shaver, Ransonville, NY.

How many in the Hause/House/Hawes family actually fought during this war is impossible to say. Muster roll calls are hard to find, but here's a list of claim awards from the Veterans of New York:²

| NUMBER | NAME | RESIDENCE | AMOUNT |

| 5,437 | Hause, George | Cameron, Steuben Co., NY | $53.00 |

| 1,198 | Hauser, William | Manlius, Onondaga Co., NY | $68.00 |

| 4,374 | Hawes, David Jr. | Beekmantown, N.Y. | $20.50 |

| 8,308 | Hawse, Abraham | Granby, New York | $18.25 |

| 4,161 | House, Chester (by admin.) | Rome, NY | $29.50 |

| 14,293 | House, Chester (by Widow) | Kendall Co., IL | $13.00 |

| 10,571 | House, Conrad | Ann Arbor, Washtenaw Co., MI | $38.00 |

| 8,886 | House, Conrad P. | Avoca, NY | $58.00 |

| 5,397 | House, David | Pamelia, Jefferson Co., NY | $78.00 |

| 9,264 | House, Harmanus (by admin.) | Ithaca, Tompkins Co., NY | $58.00 |

| 319 | House, Isaac | Onondaga Co., NY | $22.50 |

| 13,646 | House, Jacob (by Widow) | Columbia Co., NY | $73.00 |

| 7,821 | House, John | Rockland Co., NY | $58.50 |

| 2,193 | House, Joseph | Lewis Co., NY | $17.00 |

| 16,528 | House, Joseph P. | Wheeler, NY | $57.00 |

| 13,478 | House, Lewis | Canada | $73.00 |

| 14,522 | House, Reynard | Orange Co., NY | $55.00 |

| 9,356 | House, Thomas | Le Ray, Jefferson Co., NY | $60.00 |

|

The prisoners were allowed to go to the farm for water, and one day Lewis House, prisoner, met CATHERINE HOUSE, granddaughter of Loyalist Harmanus House... and they fell in love. Fortunately Harmanus wasn't around to see his granddaughter romanced by a United States House, or Lewis might've suffered the same hayfield treatment as John Bellinger!!!

On June 16, 1818, the Reverend William Sampson of St. Andrew's Church, Grimsby, united the young couple in marriage. Lewis remained in Canada, and eventually secured a piece of the (other) House family farm. How can it be incest if you're from different countries, right? (In The House Family of the Mohawk, Shaver just assumed that Lewis was the son of John, Catherine's Dad, and they were brother and sister. Nooooooot quite, but close...) Anyway, Lewis gets my BLACK SHEEP OF THE 1800's award for flocking with a relative.

Honorable Mention for this award must go to ALONZO HOUSE, who married his niece MARIAH HOUSE (daughter of his brother, ANDREW) in the mid-1800's. They had two children, Xystus and Clyne, and many grandchildren... or is that GREAT-grandchildren? And did Alonzo call Andrew "brother" or "dad?" Father's Day could be very confusing on the frontier.

After the war, the young nation to the south and the loyal British colony to the north remained separate, to develop into the societies known today as the United States and Canada, and create a House family divided (bad pun intended).

LITERARY SOURCES FOR THIS PAGE:

|

CHAPTER 1: THE HAUß FAMILY IN THE DUCHY OF SOLMS CHAPTER 2: JOHANN CHRISTIAN HAUß CHAPTER 3: THE NEW WORLD CHAPTER 4: FROM HAUSS TO HOUSE CHAPTER 5: THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION

APPENDIX #1: JOHANN RHEINHARDT HAUSS GENEALOGY APPENDIX #2: JOHANN JURRIAN (GEORGE) HAUSS GENEALOGY APPENDIX #3: HOUSE LINES IN CANADA APPENDIX #4: HAUß HERALDRY APPENDIX #5: HAUß FAMILY TIMELINE APPENDIX #6: LINKS TO OTHER SITES

APPENDIX #1: ALLIED FAMILIES APPENDIX #2: OTHER HAUSE FAMILIES APPENDIX #3: ABOUT THE AUTHOR

|