|

"Let these good pious Palat'nates, And all such strange we know-not-whats, In their wise interloping Freak, Go to the Devil's Arse a-Peak."

—From the English poem, "Canary-Birds Naturaliz'd in Utopia," published in 1709.

|

Still, as bad as the conditions were at Rotterdam, the journey to London was even worse. It was supposed to have been a voyage of under four weeks, but they didn't actually arrive in London until months later. Furthermore, if they thought the British would be prepared any better than their hosts at Rotterdam, they were in for another in what would become a long line of disappointments.

The arduous journey was already affecting the emigrants. Many were sick, most were hungry, and they all were scared, trying to find temporary shelter in a strange land where everyone spoke a different language.¹

"What freak brought these poor creatures hither is not easy to guess ... Upon whose motive they were encouraged to come hither and what they are to do now they are here, is out of my reach."

—Roger Kenyon, after visiting the Palatines at the Blackheath Camp, August 1709.

A contemporary woodcut of the Palatines attending church in London. |

What Kocherthal found in London was that the British people, convinced they were going to lose food and jobs to these new arrivals, hadn't done much to welcome the "Poor Palatines"—in fact they had rioted, and many attacked any German-speaking immigrants. Each day had grown worse, and many of the refugees were giving up, accepting offers to go to Ireland and work as share croppers. Others were returning to what was left of their homelands. But not Johann Christian Hauß. He had persevered. He could hardly picture life getting any worse... But it would.

Finally, around Christmas time in 1709, some 845 families boarded eleven ships for the long trip across the Atlantic Ocean... Where they continued to wait for a go-ahead from the queen. So Christmas was spent on a smelly, overcrowded boat.

Christmas wasn't celebrated much in England at that time, anyway. It was meant to be a day of penance and contemplation. The Germans, however, loved celebrating the holiday, and so there were probably some games and activities on the ship, despite their desperate situation. The children could have expected a visit from Pelznickel (Saint Nicholas in furs), better known as "Belsnickel." This version of Santa liked to scare children half to death, before changing character and giving them sweets. Of course, with no money, fruit or candy (let alone a barn), and with the anticipation of a long, dangerous trip across the Atlantic, the celebration was probably subdued... But the Hauß family didn't celebrate at all.

"It is supposed that Christian Hauss' first wife ... died on the voyage over, or soon after reaching these shores, as history of that period tells us that sickness and privations took many lives, both on the voyage over and the winter following."

—"The House Family of the Mohawk," by Melvin Rhodes Shaver. Publisher: St. Johnsville: Enterprise, 1933. Chapter 1, Page 3

|

The remaining Hauß family waited to discover their fate from the British authorities, but an answer wasn't forthcoming. The Palatines remained onboard their docked ships for several more months before actually sailing—just waiting, starving and grieving.

The ships continued to sit for a total of six long months in the Thames. Finally, in April of 1710, the convoy set off for the New York Colony. (This flight from Britain would actually create a misperception in the family history, with Hauß tradition proclaiming, "that six brothers came from England to America together," causing later descendants to assume they were British.)

The Savoy Chapel, once part of the Savoy Hospital dedicated in 1512, as it looks today. The German Lutheran congregation of Westminster (now at 10 Sandwich Street, London, WC1H 9PL, crossing Thanet Street, near St Pancras) was granted royal permission to worship here in the 1690s, next to the hospital and prison. Pastor Irenaeus Crusius dedicated the chapel on the 19th Sunday after Trinity 1694 as the Marienkirche, or the German Church Of St. Mary-Le-Savoy. It was then called the Savoy German Lutheran Church off the Strand. This chapel seviced the Palatine immigrants, and recorded the death of "Mrs. Haus" on December 25, 1709 in its Churchbooks. The chapel is now in use by the Church of England as the church for the Duchy of Lancaster and Royal Victorian Order. |

"When they are buried all the attendants go singing after the corpse and when they come to the grave, the coffin is opened for all to see the body after it is laid in the ground they sing again for some time and then depart. They carry grown people upon a bier and children upon their heads."

—Daniel Defoe: A brief history of the poor Palatine refugees, 1709

|

|

|

Seeing the wretched state of the starving, sickly, disease-infested passengers onboard the ships (not to mention 500 rotting bodies awaiting burial), the New York City Council quarantined all of them offshore on Nutten (now Governor's) Island for almost four months without food and supplies. Obviously, this did nothing to improve their health, and 250 more perished from the fever, which was to be known for many years in New York City as "Palatine Fever."

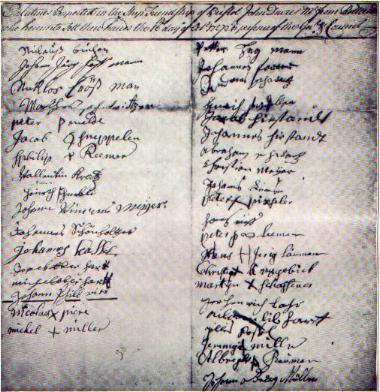

"23. Sept. 27th: Christian HAUSS, widower, a carpenter, of Alten-Staeden, near Wetzler, duchy of Solm and Anna Catharina BECKER, widow of the late Johann BECKER, of Duernberg, near Dietz, commune Schaumburg."

—page 41 of Reverend Joshua Kocherthal's church record.

|

On the Colonial frontier, the loss of a spouse required quick remarriage, as men and women had too many differing responsibilities (the men outside of the house, the women inside of the house) to be able to raise children alone. Marriage was a business contract, and had only been "sanctified" by the church for about 150 years. "Mourning" was a luxury that was unavailable to Europeans and Colonists until the Victorian era. Speedy remarriage was the rule, often within months of a spouse's death, regardless of gender.

Anna was in the same situation as Johann Christian Hauß. She was the widow of Johann Becker, who had also died during the journey to America. She was from an area of the Holy Roman Empire on the Lahn river. The Grafschaft (County) Dietz (or Diez) became part of Nassau-Dietz, which was elevated to the rank of Fürstenland under the name of Nassau-Oranien in 1388; and since 1747 the ruling family in Nassau-Dietz has reigned in the Netherlands. So back in Europe, the residents of Johann's and Anna's villages might have been at war with each other on several occassions—but in the New World, circumstances helped to bring these "Palatines" of differing homelands, religions and even languages together. The honeymoon accommodations were primitive at best, but since Johann was a carpenter, I'm sure the threshold he carried her over was a sturdy one.

|

So the newly-expanded Hauß family faced another hard journey, this time on roads that were little more than footpaths cut through a forest of dense pine forest, to get to the barren wasteland where they were to live. They pulled small hand carts and wagons, and carried all of the food and supplies they could scrounge up on their backs (minus weapons and tools, which the British confiscated, to keep them from running off or revolting).

By October, these poor, weary immigrants were clearing the land and building small huts for shelter. But it was hard to build houses without proper tools: Some lived in caves that were dug into hillsides, with brush covering the entrance. Others lived in mud huts or cabins made out of very rough logs.

Of course, being an experienced carpenter from war-torn Solms, Johann Christian Hauß and his sons were used to making due in such desperate conditions, and probably built a strong cabin for themselves out of wood and stone, held together by clay and/or mud mixed with chopped straw. (And if the land offered to the Palatines had anything in abundance, it was rocks.) Then they probably helped the other settlers create shelter from the fast-approaching winter. Most homes had only one room, which had a central stove or fireplace for cooking and keeping warm. A wooden bench was placed nearby so the family could sit and keep warm during the intense winter months, and that fire was kept burning all the time.

"(The men would) dig a square pit in the ground, cellar fashion, six or seven feet deep, as long and broad as they think proper.; case the earth all round the wall with timber, which they line with the bark of trees or something else to prevent the caving-in of the earth; floor this cellar with plank, and wainscot it overhead for a ceiling; raise a roof of spars clear up, and cover the spars with bark or green sods so that they can live dry and warm in these houses with their entire families for two, three or four years, it being understood that partitions are run through these cellars, which are adapted to the size of the family."

—Cornelis Van Tienhoven, secretary of New Netherland, describing the "dug-outs" in which the Palatines lived, in an official report sent to the Hague.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

According to a manuscript in the Public Record Office in London, Johann Christian Hauß was listed as one of 847 debtors to the British Government for subsistence given them in New York City or in Hudson River settlements after their arrival there between 1710 and September 1712. So when spring arrived, the Hauß family began the long process of repaying their debt to the British: They were "redemptioners," or indentured servants, and had to work for a period of four to seven years to pay off the cost of their ocean voyage and relocation before they could earn their Freiheiten (rights as citizens—sort of a combination of Bürgerrecht and 'freedom'). The conditions were harsh; for instance, if an indentured child died before the contract was completed, the child's parents or siblings might be forced to work the remaining years of that contract, in addition to their own. Indentured servitude, unlike slavery, was entered into voluntarily—but you wouldn't know that by reading colonial newspapers, which were filled with advertisements offering rewards for redemptioners who had run away from their masters. Still, the Palatines could earn their way out of servitude—after which they were promised 40 acres each in "the land of Scorie"—rich Indian land had at one time been considered for settlement by Gov. Hunter. To Johann Christian Hauß it must have literally been the promised land. But until that day, he was to live in "Haysbury," one of seven Palatine camps stationed along the Mohawk River:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Christian and the others collected what little tar and turpentine they could wring from the trees, which were unhealthy and rooted weakly into the sand. They would then report to Fort Hunter at the confluence of Schoharie Creek and the Mohawk River, where in exchange they were given the "queen's bounty"—meager rations of salted meat, bread and watery beer. (Not unlike my own diet in 2005.)

The Pitch and Tar project was a disaster. Tar was usually made at that time from the pitch of the Southern Georgian Pine. The northern or White Pine contains little pitch from which to make tar. Beyond that, the Palatines were as ill-suited for the work as the rocky land. They were raised to cultivate nature's bounty in farms and wineries—not destroy it for profit. Governor Hunter was soon forced to dip into his own money to keep the experiment afloat, and then looked to cost-cutting measures. He instructed the overseers to only distribute beer to the working men, and not their families (a great insult to the Palatines' customs). Then he started plans to put all of the new widows and orphans to work and "be no longer a burden." He actually started binding the children out to local farmers, effectively destroying many Palatine households—because there proved to be no differentiation between orphans and the children of poor parents. Most of Christian's (and Anna's) children were grown, but he was apparently able to keep the rest—and they were about the only possessions he still had. His family, as recorded on Governor Hunter's subsistence lists:

|

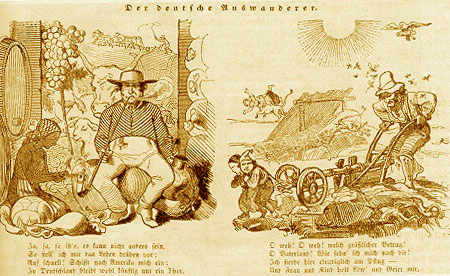

Dream vs. reality in "The German Emigrant," from the magazine Fliegenda Blätter (1845). |

Christian and his family were pawns in that effort, just as exploited as the Indians, but with even fewer rights (at least the Indians were allowed to leave the Fort).

After crossing the Atlantic, surviving disease, cold, and angry Indians, Christian and Co. were still poor, still cold, still in danger, still slaving under a foreign ruler—and now on top of everything else, heavily in debt. They wouldn't be allowed leave the compound until all of their travel debts to the British government were repaid. But there was a reward for all of this: Christian's forty acres in the land of Scorie—land to settle and build on, that his sons could develop—and then their sons, too. Christian and his second wife, Anna Catherine, had at least two children, as well. Women married during indentured servitude were supposed to be bound to celibacy for five to seven years, but her widow status apparently excluded her from this, because she and Christian had children right away. The two we know of were:

CHILDREN OF JOHANN CHRISTIAN & ANNA CATHARINE HAUSS |

Finally,

in late 1711, the Whig party lost control of the British Government to the Tories,

so support for Gov. Hunter declined, and, incredibly... the situation grew even worse!

The entire "Pich and Tarr" project was shelved. Without Hunter's continued

"financial support," the Palatines were soon left to their own devises...

of which they had none. They weren't allowed to own farming tools, guns, or anything

that would've allowed them to fend for themselves.

As for

the promised land—the Schoharie Valley, there was worse news: Jean Cast,

Governor Hunter's assistant commissary agent (meaning he was the guy who passed

out the tools, rations and the rags to wear), informed the Palatines that the

"Scorie" land would only be given to them after they had worked

off the cost of their transportation to New York, after the charges for

their food and drink had been cleared, after Livingston had earned a profit,

and cruelest of all, after the cost of the coffins for the ships' dead had been discharged. Christian and Anna Catharina, who had both lost a spouse on the journey, felt they had paid more than enough for their forty acres, so they and the other Palatines began to plot an alternate plan...

The Mohawk River at Stone Arabia, Johann Christian Hauß's eventual destination, as it looks today. |

"We came to America to establish our families—to secure lands for our children on which they will be able to support themselves after we die."

—Palatine refugees to their overseers in "Documentary History of the State of New York" (Albany, 1849-51)

|

While slogging through deep snow and dense forest in freezing temperatures, and running from the "law," it must have seemed to Johann Christian Hauß that life hadn't changed a bit for him since leaving Solms-Hohensolms.

For two weeks the desperate escapees cleared a path west of Albany "with the utmost toyle and labour," through the wilderness of the Helderbergs, down Fox's Creek... to a small brook where they stopped for "a general purifying"—cleansing themselves of all the grime and bugs they had accumulated on the journey (the brook is still known today as "Louse Kill" in honor of the event).

They were given food and shelter by friendly Mohawk Indians, and bartered for their land (which, as usual in those times, involved liquor)...Who knows, maybe the Indians sympathized, because they had been screwed over by the British, too. Many influential figures among Indians and whites crossed over from one cultural sphere to another, speaking various European and Indian languages and intermarrying, and forming political alliances between the two rapidly merging worlds. In New England some Indians still lived in traditional wigwams, but they filled them with European-manufactured furniture and decorative items. Some members of the Oneida tribe of the Iroquois confederacy practiced Presbyterianism, although simultaneously retaining traditional beliefs and rituals. Some Indians adopted European dress but retained the loincloths and nose rings of their own cultures.

|

If Hunter wasn't already angry that his redemptioners had bolted from his fort and left him 20,000 Pounds in debt from the failed "Pitch and Tarr" project, now they were squatting on his most profitable land! "Being arrived and almost settled, they received orders from the Governor not to goe upon the land, and he who did so should be declared a Rebel."

Clear title or not, Johann Christian Hauß cleared the land for a farm on the land he was promised. Having been forced to leave behind what few tools he had, he made do with whatever he could make from the forest... and on several occasions he and the other pioneers forcibly ejected land agents, including Governor Hunter's sheriff, as later reported by John M. Brown: "But when the Sheriff began to meddle with the first man, a mob of women rose, of which Magdalene Zee was captain. He was knocked down and dragged through every mud pool In the street; then hung on a rail and carried four miles, thrown down on a bridge, where the captain took a stake out of the fence and struck him in the side, that she broke two of his ribs and lost one eye; then she p*ssed in his face, let him lie and went off."

So the relations between the Palatine rebels and their former overseers deteriorated even further. Some had prices on their heads, and all the men avoided going into town for supplies, fearing arrest by the British.

Palatines believed that property didn't belong so much to an individual as to families and clans. While individually held, property and liberty were defended by the community. This value system would be ingrained into the Haus family for centuries: Land was acquired, fought for, settled, and eventually divided among the children with each successive generation—when there was no more land to divide, they moved west toward open country.² And with no legal land available, Christian's sons began to move on: His son Rheinhardt ("Rynier Hous") was Naturalized on January 10, 1715, and was listed as working as a yeoman in Phillipsburgh. Eventually he moved to Hackensack, near his Becker stepbrothers, and his own brother Johannes, in Haverstraw.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Meanwhile, the Palatines on the frontier adopted Indian ways in the form of clothing, canoes, and native foods. They grew Indian corn and hunted just as Native Americans did. They soon created and wore breechcloths and leggings and were quite proud of their ability to hunt and live off the land like Indians.

Wherever Christian's farm was, it had to be self-sustaining, as carpentry work wasn't very lucrative, seeing as his clients had no money. Fortunately, the British had been wise in their choice of destination for the Palatines: Eastern North America is quite similar to the Rhineland, and therefore an ideal fit for the Germanic farmer: The soil and climate are similar, and the land almost identical—prime flat farmlands cover the Hudson river, just like the Rhine, with the same kinds of maples, oaks, beeches, and ashes in the low hills. So the Palatines didn't feel out of place, and knew how to create a farm.

Everything on the Hauß farm had to be made or bartered. So, to create a self-sustaining enterprise, on top of the pastures and grazing land that Christian reserved for the livestock (providing meat, milk, dairy products, and leather), he built pens to raise chickens, geese and ducks for eggs, meat, and feathers (for bedding).

Surplus fats from the animals were used to make candles and soap. Shad and herring were caught making their runs up Schoharie Creek to the river, then pickled or smoked for later use. Wild pigeons were shot by the hundreds and preserved by pickling and smoking, as well.

To round out the diet, the Hauß family probably grew wheat, corn, rye, and potatoes in his fields. Turnips, beets, cabbages, onions, pumpkins and peas filled the garden, with an herb garden as well, to grow Anna's food seasonings and "simples"—herbs used as medicine. She and the daughters would have picked berries growing wild in the forest. Tobacco would also have been grown for smoking, which almost all of the Palatine men and women enjoyed. Maple sap and honey were used as sweeteners. Hops were used to brew beer, which in most homes was more popular than water.

Tools were all homemade and crude—metal plows were not available, so Christian tilled the earth with a tree crotch shod with iron. Leather hides for tools were cured in the farm tanning vat.

Everything was stored in the barn, which had to hold enough autumn crops and salted meat to last through the long, brutal winters. In fact, the stone barns were usually better-constructed and more valuable than the log houses, for the simple reason that you could survive in a barn without a house, but not in a house with no barn to supply the necessities of life.

As for furniture, there was plenty of wood—maple, cherry, and (of course) pine—which was also needed to heat the house in the fireplace and stove.

Times were obviously rough, but you can't help thinking how cozy the nights must have been with Anna Catharina cooking a late dinner, with the kids nestled around the fireplace and Christian smoking his pipe and telling stories of the Old Country.

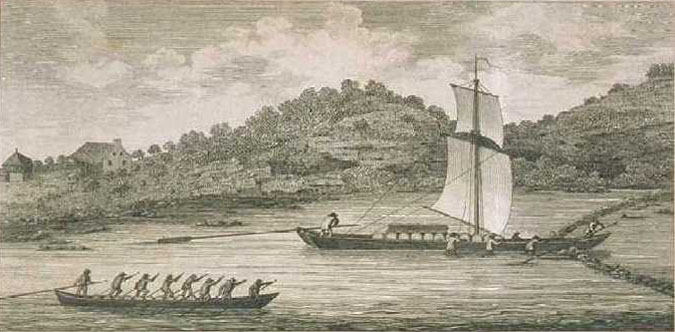

"A View of the Boats & manner of navigating on the Mohawk River." (Engraving by Christian Schultz.) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Then in 1715, it was enacted “That all persons of foreign birth professing Christianity could be naturalized by taking the oath of supremacy and subscribing the test and repeating the oath of abjuration. And Johann Christian Hauß, now free of indentured servitude, did just that with his friend, Heindrick Klock. (Sadly, the act was not to be construed to set at liberty any bondman or slave.) The religious qualifications were strictly enforced and Catholics were put under the ban.

On the 11th of October, 1715, he was Naturalized as a citizen of the British Empire (as "Christian Houys" of Albany County).

You may wonder why, after everything the British had done to Johann Christian Hauß, that he would have wanted to become a Naturalized citizen. The main reason was to protect the family land. England divided the people who dwelt within her borders into three classes—natural-born subjects, aliens, and denizens. But thanks to a British act passed in 1700, His Naturalized status enabled him to hold lands as well as transmit property to his children. This placed his children in the colonies on a par with subjects living in England itself.

Of course, there was another reason, too: "Liberty." Mind you, Palatines of the Reformed Church defined "liberty" in a very different way than we do today. Freedom was a deeply personal matter. It meant that they could make decisions for themselves without Hunter or Livingston breathing down your neck, but with a willing and unbending obedience to the government protecting them. Although Johann Christian Hauß and his sons had deep disagreements with the British, they still became citizens under the Crown, in opposition to the French government that had pillaged and destroyed their homeland. After six years of traveling without a home or flag, then working as a virtual slave, he could now at least say he belonged somewhere, whether he liked the local government or not, and could finally get some Bürgerrecht. Johann Christian Hauß was finally a free man!

Then in 1722, after many years of litigation, Gov. Hunter's successor, Gov. William Burnett, decided on a new strategy with the Palatines squatting in Scorie: He purchased new land in the Mohawk Valley for them to settle on legally. In 1723, 100 heads of families from the work camps were settled on 100 acres each in the Burnetsfield Patent midway in the Mohawk River Valley, just west of Little Falls. They were the first Europeans to be allowed to buy land that far west in the valley. He informed Britain that he would allow about sixty families that had been the strongest supporters of the crown to buy land at a decent price. Among them was the Hauß family.

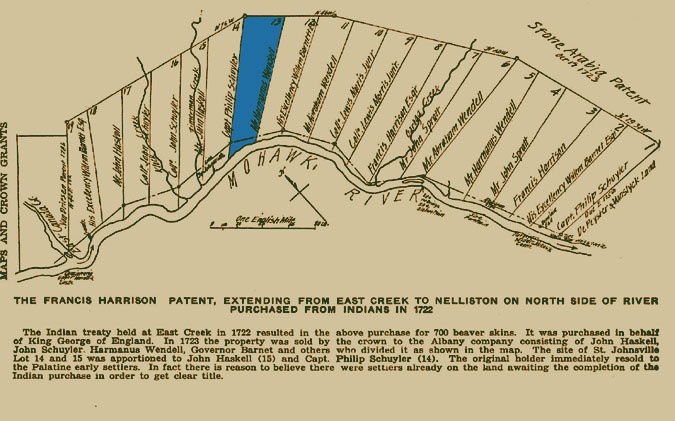

"In the year 1725 on August 26, we find in the Albany County records a transfer executed by Harmonas Wendell a parcel of land, being part of Harrison's Patent and lying near the mouth of Little Canada Creek, to Christian Haus and Hendrick Klock, Albany County deeds, Book 7, page 87, etc. The record of this transaction was taken from the St. Johnsville Reformed Church Book."

—"The House Family of the Mohawk," by Melvin Rhodes Shaver. Publisher: St. Johnsville: Enterprise, 1933. Chapter 1, Page 3

As recorded in The House Family of the Mohawk, Christian and friend Hendrick Klock (who was naturalized with him in 1715) purchased 650 acres of land along the Maquas (Mohawk) River (on lot #13, in blue, above) on August 26, 1725, to be divided equally, with one acre left over for a church: "That is to say to each of them one full mojety or undivided half part of the whole in two Equall parts to be devided," according to Albany County Deeds, Book 7, page 89, from Harmanus Wendell for L-250 (probably English pounds—which seems like a good deal, until you read that the entire patent was purchased from the Indians for 700 beaver skins). How he could afford to pay such an amount is unknown—the only people with that much money in the area were the aristocracy and Indian traders. But finally, nearing the age of sixty, after a brutal life of servitude and deprivation, Christian would own a large piece of fertile property that was going to be his alone—that he and his family could finally prosper on... that could be handed down to his children, and last through the coming generations...

...But it wasn't to be. What The House Family of the Mohawk authors didn't know is that Harmanus Wendell died before the deed could be executed, and the property went instead to Harmanus' eldest son, Jacob Wendell, who didn't want to sell. The stress of it all must have been too much for Johann Christian Hauß. When the property finally changed hands, seven years later, he had either died or transferred the titled to Heinrich Walrath. His seemingly unending search for the promised land finally did end—he disappeared from the public record after failing to purchase the land, leaving his sons to fulfill his dream of Bürgerrecht.

|

CHAPTER FOUR: HAUSS TO HOUSE: The family is Americanized, right along with the name.

¹—It was in England that the spelling of the family surname would first be mangled, twisted, re-spelled, and forever changed. "Hauß" was simplified to "Haus" and then remolded into a variety of British spellings like "Hawes," "House," "Hays" and countless other variations. But since it's doubtful that Johann Christian Hauß or anyone in his family could spell, they never complained.

²—According to ProGenealogists.com, out of the Mormon Family History Library in Utah, the earliest subsistence lists in the colonies, such as the ones used by Governor Hunter in New York, were taken directly from the passenger lists, and emigrants were listed in the same order. With this in mind the Hunter Subsistence Lists were used to compile reconstructed passenger lists. Since there were 847 individuals/families in these lists and 11 ships, that would mean there were about 77 of these names per ship. Some ships probably had more and some less, due to sicknesses and deaths on board. But a careful studying the Hunter lists leads to the idea that the names are listed roughly chronologically in the order of their arrival at New York.

³—According to Property and Boundary Mapping in Colonial New York, by David Yehling Allen, Revised 10/23/10: "The most distinguishing feature of British maps of colonial New York is their preoccupation with land ownership... This focus on land ownership and partition reflects the growth of population under British rule, as well as the characteristically English desire of poor men to become independent farmers, and of rich men to become landed gentry. Land was also the primary source of wealth during the colonial period, and land speculation became a popular form of gambling in colonial New York, playing much the same role as the stock market does today."

SOURCES FOR THIS PAGE:

- The Mohawk Dutch and the Palatines, by Milo Nellis. 1951.

- History of 18th Century Germantown, by Walter Miller.

- The Mohawk, by Codman Hislop. Syracuse University Press. 1948, 1989.

- A Brief Sketch of the First Settlement of the County of Schoharie by the Germans, by John M. Brown

- White Cargo. the Forgotten History of Britain's White Slaves in America, by Jordan, Don And Walsh, Michael. Publisher: New York Univ. Press Date Published: 2007.

- Palatines, Liberty and Property: German Lutherans in Colonial British America, by A.G. Roeber. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, 1998.

- Dutch Houses in the Hudson Valley before 1776, by Helen Wilkinson Reynolds. Dover, 1965.

- Trappers of New York; a biography of Nicholas Stoner and Nathaniel Foster, by Jeptha Root Simms. Albany: J. Munsell. 1850.

- Cultural adaptation in Colonial New York: The Palatine Germans of the Mohawk Valley, by Robert Kuhn McGregor; "New York History Journal" Volume 69, number 1. January 1988

- The Story of the Palatines, An Episode in Colonial History, the largest immigration in number of any Colonial arrival, the settlers from the southwestern district of Germany known as Palatine, by Sanford H. Cobb, dedicated to the Children of the Palatines, the author's parishioners in the High Dutch churches of Schoharie and Saugerties. New York & London, G. P. Putnam's Sons. 1897

- Heads of Households of the 1709/10 Palatines Who Went from Germany thru the Port of Rotterdam to London ," The Lost Palatine," no. 10 (1983), by Gail Breitbard. Page: 8

- "The Embarkation Lists from Holland." In Early Eighteenth Century Palatine Emigration, by Walter Allen Knittle. Philadelphia: Dorrance & Co., 1937, pp. 248-274. Reprinted by Genealogical Publishing Co., Baltimore, 1965. Repr. 1982:

- Name: Johann Haus; Year: 1709. Place: England or America. Family Members: 3 children. Page: 272.

- Johann Adam Haus, Year: 1709. Place: New York (p. 255). This man is either listed as "Hoff" or "Hussmann" on the Hunter Subsistence Lists in 1710 and 1712. NOTE: In Palatine Families of New York, Hank Jones lists the last name as "Haas," and his family has a different point of origin than Johann Christian Hauß. While their last names look similar, they have totally different meanings in German. Haas is Dutch, German, and Jewish (Ashkenazic): from Middle Dutch, Middle High German hase, German Hase ‘hare’, hence a nickname for a swift runner or a timorous or confused person, but in some cases perhaps a habitational name from a house distinguished by the sign of a hare. As a Jewish name it can also be an ornamental name or one of names selected at random from vocabulary words by government officials when surnames became compulsory.

|

|

FOREWARDS: BY MELVIN RHODES SHAVER AND JEFF HAUSE CHAPTER 1: THE HAUß FAMILY IN THE DUCHY OF SOLMS CHAPTER 2: JOHANN CHRISTIAN HAUß CHAPTER 3: THE NEW WORLD CHAPTER 4: FROM HAUSS TO HOUSE CHAPTER 5: THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION

APPENDIX #1: JOHANN RHEINHARDT HAUSS GENEALOGY APPENDIX #2: JOHANN JURRIAN (GEORGE) HAUSS GENEALOGY APPENDIX #3: HOUSE LINES IN CANADA APPENDIX #4: HAUß HERALDRY APPENDIX #5: HAUß FAMILY TIMELINE APPENDIX #6: LINKS TO OTHER SITES |