|

The surname of Putnam is English: it's a habitational name from either of two places, in Hertfordshire and Surrey, called Puttenham, from the genitive case of the Old English byname Putta, meaning ‘kite’ (the bird) + Old English ham ‘homestead’.

The coat of arms have been borne by the Putnams from early times, and are first ascribed to SIR GEORGE PUTENHAM of Sherfield. The arms are Sable, between eight crosses crosslet-fitchee (or crusily-fitchee), argent, a stork of the last, beaked and legged gules. The crosses were a token of the Crusades, the holy wars of 1096-1291, and were considered a bearing of the highest honor, expressing the badge of Christianity and the four-fold mystery of the cross. The color silver indicated peace and sincerity. The stork was the emblem of filial duty, in as much as it rendered obedience and nourishment to its parents, and was also the emblem of a grateful man, and in ancient times this bird was treated with great respect. The Crest is a red wolf’s head. This symbol was an ancient and unusual bearing, said to denote those valiant captains that do in the end, gain their attempts after long sieges and hard enterprises. The wolf was an animal that was weary and careful in attack, and therefore one that was dangerous to approach or obstruct. The color red was symbolic of military fortitude and was also the martyr’s color. (Each Putnam could have slight variations on their coat of arms.

The family was well-known in war and in the arts: Elizabethan writer, courtier and lawyer George Puttenham (1529-91) was reputed to have authored the acclaimed anonymously written Arte of English Poesie in 1589, a book closely related to the Shakespeare plays. In fact, an increasing amount of evidence has surfaced to suggest that Puttenham authored the Sonnets, which have traditionally been attributed to Shakespeare.

So obviously, our line of the family started proudly. It stretches back to the ancient lords of Putenham, up through RICHARD PUTNAM of Woughton on the Green, who died in 1556-7. He and his wife, JOAN, were the parents of JOHN PUTNAM of Rowsham, who died in 1573, and who in turn was the father of NICHOLAS PUTNAM of Wingrave and Stewkley, whose son, JOHN PUTNAM of Aston Abbots, emigrated to Salem, Massachusetts in 1640. From there on, the family name would forever be tied with deceit, murder, and flat-out evil.

Richard's will, dated 12 Dec. 1556, proved 26 Feb. 1556/7, devised his house in Slapton ''to Joan my wife for life, with remainder to John my son.'' He also leaves a legacy to his son John and the latter's wife and their children. He further names his son Harry and his daughter Joan. The executor and residuary legatee was his son Harry Putnam, and the overseers were "John Putnam my son" (our ancestor) and Richard Brinclow (Arch. Bucks, Bk. 1556-7, fo. 35).

JOHN PUTNAM was born 1515 in Wingrave, Buckinghamshire, England. He married a woman named MARGARET (last name unknown), who was born about 1517 in Wingrave. John was assessed at "Wingrave with Rowsham" on 18 Feb. 37 Henry VIII (1545/6) on £7 in goods, for 4/8 (L. S. 78/148) and again on 20 April 3 Edward VI (1549) for relief on £12 goods, 12/ (L. S. 79/163). John's will, dated 19 Sept. 1573, proved 14 Nov. 1573, names his sons Nicholas, Richard and Thomas. To his son Richard he left his house in Wingrave with eight yards of meadow lands and a close called "Smythes Green" (Arch. Bucks, Filed Will). The Wingrave Court Roll for 1573-4 shows that at his death John Putnam held a house there of the Honor of Berkhampstead by knight's service, which house was "sometime the town house, with a close called Smythes Green and 8 yards of meado in franchise and 3 acres of arable land. Richard Putnam is his heir, of full age, whereby 4d is due the Queen for his relief." (Court Rolls and Ministers' Accounts, Berkhampstead, Portfolio 155, no. 38.) It must here be noted that Richard was not the eldest son, but is described as heir because he was devisee of this land by his father's will.

NICHOLAS PUTNAM was born about 1540/1554 in Wingrave, Bucks Co., England. He died 27 Sep 1598 in Wingrave, Bucks Co., England. Nicholas married MARGARET GOODSPEED on 30 Jan/Jul 1577 in Wingrave, Bucks, England. Margaret was born 16 Aug 1556 in Wingrave, Bucks Co., England. She died 8 Jan 1619 in Wingrave, Buckinghamshire.

They had the following children:

KIDS OF NICHOLAS PUTNAM AND MARGARET GOODSPEED |

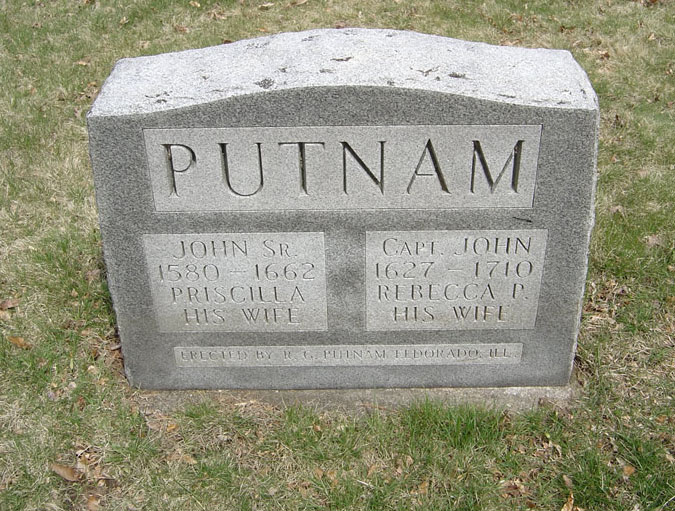

John

Putnam was christened on January 17, 1579/80 in Wingrave, Buckinghamshire, England.

He was a Buckinghamshire yeoman, who came from Aston Abbots in Bucks, a parish

lying in the eastern part of the county near the Hertfordshire border and only

a short distance from Puttenham, the original home of the family. His father Nicholas'

will, dated 1 Jan. 1597/8, proved 27 Sept. 1598, gave John his lands in Aston

Abbots (Arch. Bucks, Filed Will). He then married PRISCILLA

GOULD sometime around 1611 in England. (She was born @ 1586, the daughter

of Richard Gould and Elizabeth.) John died December 30, 1662 in Salem, Essex County,

Massachusetts.

They

had the following children:

KIDS OF JOHN PUTNAM AND PRISCILLA GOULD |

JOHN

PUTNAM Younger was christened on the 27th of May, 1627, in Aston Abbotts, Bucks,

England. John married REBECCA PRINCE on 3 Sep 1652 in Salem, Essex, Massachusetts,

(she was the daughter of JAMES PRINCE and MARY.

Rebecca PRINCE was born about

1630. John died on the 7th of April, 1710, in Salem—not a moment too soon

for a lot of people:

John

was not a nice guy. He and his brother Thomas orchestrated a lot of the arrests

during the Salem witch trials, using them to get rid of (ie: execute) a lot of

their business rivals, or people they just didn't like, including rival farmers,

their former minister, and even the BASSETTS and PROCTORS,

who were also our ancestors. Whether they did this because they were ruthless

enough to use a volatile situation to kill off anyone they didn't like, or because

John was just backing up his brother in defense of his child, or because their

Puritan instincts deluded them into thinking anyone who disagreed with them was

aligned with the devil, we may never know. But the facts are that the Putnams

were instrumental in the deaths of a lot of innocent people.

The

most famous case of this would have to be the trial and death of a minister named

George Burroughs, who originally was a preacher in Casco. A non-ordained minister,

Burroughs graduated from Harvard College-now Harvard University- in 1670, according

to a report published by Douglas Linder of the University of the University of

Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. In August of 1676, Indians attacked the town

during King Philip’s War, and captured and killed thirty-four members of

the community. Burroughs remained in Casco another four years, and helped the

ravished community rebuild their lives and businesses. Then in 1680 he accepted

the call to the small church in Salem, Massachusetts. "Salem Village might

be safer from Indians, but its own dangers were to prove, at least for George

Burroughs, deadlier." (Quote from Hill, Frances, A Delusion of Satan:

The Full Story of the Salem Witch Trials. New York: De Capo Press, 1995, page

125.)

Salem was in the midst of change: a mercantile elite

was beginning to develop, prominent people were becoming less willing to assume

positions as town leaders, two clans (the Putnams and the Porters) were competing

for control of the village and its pulpit, and a debate was raging over how independent

Salem Village, tied more to the interior agricultural regions, should be from

Salem, a center of sea trade.

George Burroughs could have

been aware of the difficult situation at Salem Farms. But an opposing faction

to his appointment as minister refused to pay their tithes, so Burroughs did not

receive payment. Allotted only sixty pounds per year, most of which was to be

for fuel and provisions, he didn't not have enough food, fuel, or money with which

to care for his family. When the payments stopped coming in, Burroughs stopped

preaching.

Despite these unfavorable circumstances, Burroughs

tried to help the community by encouraging them to build their own church. This

goal did not see its fruition, however, because his wife died during their stay

at Salem Farms. .

Discouraged, Burroughs left the town in

1683, returning to Casco. At the time of his departure, the town owed Burroughs

over thirty five pounds. Having drawn against this to pay for the funeral of his

wife, he arranged with Deacon Nathaniel Ingersoll to pay John Putnam fifteen pounds

when the funds in the church treasury were sufficient. According to Peter Charles

Hoffer in his book, The Devil’s Disciples: Makers of the Salem Witchcraft

Trials (p. 48), "Burroughs had, however, offended Captain John [Putnam]

by refusing to preach unless he was paid and was openly planning to leave. Captain

John, joined by Lieutenant Thomas (Putnam)..., first petitioned the court to force

Burroughs to stay. This failed, and Captain John then filed suit."Shortly

after his departure for Falmouth, Maine, the authorities of Salem Town arrested

George Burroughs for defaulting on his payments.

When Burroughs

returned to Salem to settle the issue of the owed money, he learned that John

Putnam had issued the warrant for his arrest. John Putnam recited to the court

debts that seemed extraordinary. Nathaniel Ingersoll, a cousin of Putnam, rose

in the defense of Burroughs, saying the debts owed Putnam by Burroughs were none.

It was common knowledge that the village owed Burroughs money for the services

he rendered. Because of this, Burroughs owed different villagers who had lent

him money or supplies in his time of need. There was no direct debt to John Putnam.

"It could be that John Putnam’s action was aimed not so much against

Burroughs himself as against those who had been withholding what was owed him.

If Burroughs were not paid, Putnam would also lose out…Such tactics [as the

imprisonment of Burroughs] suggest a bullying nature that is feeling frustrated,

threatened, and vengeful." What the Putnam brothers may also have seen in

George Burroughs was an educated man, and they may have been threatened by his

obvious intellectual superiority.

The dispute was settled

when the court ruled that Burroughs, who left almost penniless, could not be expected

to pay all his debts, wrote Wells historian Hope Shelley. "Within nine years

Putnam would have his revenge," Shelley wrote.

The

Putnams and their family allies had little to do with Salem Town, and saw no need

for their "cosmopolitan outlook." Resentment of the mercantile success

of the town allowed the Putnams to forge an elite that remained in control of

Village affairs for years. "Their most prominent members were men whose names

were to appear again and again on the complaints to the magistrates that led to

witchcraft arrests: Thomas Putnam, John Putnam Junior, Thomas’s brother-in-law

Jonathan Walcott, and Walcott’s uncle, the innkeeper Nathaniel Ingersoll."

Straight-laced and self-righteous, the family placed themselves at the forefront

of the social and political circles of the village. Exhibition of the influence

of the Putnam family power is in the various positions they held: Village Committeemen,

deacons, church elders, among others.The Putnam brothers had a habit of working

together "in an aggressive but underhanded manner to take down an enemy."

This

contempt in the Putnam family forces the question regarding the validity of the

charges alleged against those who were enemies of the Putnam family. The accusation

and arrest of many innocent people could have emerged from jealousy and resentment

found in this powerful family, known as "the chief prosecutors in this business."

It may not be that their perceived power went far beyond the accusations, because

those who spoke out against the witches were not always under the influence of

the Putnams. This is clear in the case of George Burroughs, because though many

spoke out against him during his trial, the Putnam family did play perhaps the

largest role in his arrest and trial proceedings.

By 1688,

John invited Samuel Parris, formerly a marginally successful planter and merchant

in Barbados, to preach in the Village church. The only good thing that can be

said for Samuel Parris is that he keeps the Putnams from being the most despicable

people in Salem.

A year later, after negotiations over salary,

inflation adjustments, and free firewood, Parris accepted the job as Village minister.

He moved to Salem Village with his wife Elizabeth, his six-year-old daughter Betty,

niece Abagail Williams, and his Indian slave Tituba, acquired by Parris in Barbados.

Tituba

was an Indian woman, not (as commonly believed) a Negro slave. She was originally

from an Arawak village in South America, where she was captured as a child, taken

to Barbados as a captive, and sold into slavery. It was in Barbados that her life

first became entangled with that of Reverend Samuel Parris. She was likely between

the age of 12 and 17 when she came into the Parris household. She was most likely

purchased by Parris from one of his business associates, or given to settle a

debt. Parris, at the time, was an unmarried merchant, leading to speculation that

Tituba may have served as his concubine.

Tituba helped maintain

the Parris household on a day-to-day basis. When Parris moved to Boston in 1680,

Tituba and another Indian slave named John accompanied him. Tituba and John were

married in 1689 about the time the Parris family moved to Salem. It is believed

that Tituba had only one child, a daughter named Violet, who would remain in Parris's

household until his death.

Twelve-year-old Ann Putnam, daughter

of Thomas, would meet with other local girls at the Parris house. Ann was in many

ways the leader of the “circle girls,” the young girls whose accusations

sparked the Salem witch trials. During the winter of 1692, the circle girls gathered

secretly at Reverend Parris’s house for evenings of storytelling and magic

with the Parris slave, Tituba. One of the fortune-telling games was to drop an

egg white into a glass of water and see what shape it took. One evening, Ann saw

the shape of a coffin. Soon afterwards Ann, Betty Parris, and Abigail Williams

started behaving strangely—babbling, convulsing, or staring blankly.Sometime

during February of the exceptionally cold winter of 1692, young Betty Parris became

strangely ill. She dashed about, dove under furniture, contorted in pain, and

complained of fever. The cause of her symptoms may have been some combination

of stress, asthma, guilt, child abuse, epilepsy, and delusional psychosis, but

there were other theories. Cotton Mather had recently published a popular book,

"Memorable Providences," describing the suspected witchcraft of an Irish

washerwoman in Boston, and Betty's behavior in some ways mirrored that of the

afflicted person described in Mather's widely read and discussed book. It was

easy to believe in 1692 in Salem, with an Indian war raging less than seventy

miles away (and many refugees from the war in the area) that the devil was close

at hand. Sudden and violent death occupied minds.

Talk of

witchcraft increased when other playmates of Betty, including Thomas Putnam's

eleven-year-old daughter Ann, seventeen-year-old Mercy Lewis, and Mary Walcott,

began to exhibit similar unusual behavior. When his own nostrums failed to effect

a cure, William Griggs, a doctor called to examine the girls, suggested that the

girls' problems might have a supernatural origin. The widespread belief that witches

targeted children made the doctor's diagnosis seem increasing likely.

A

neighbor, Mary Sibley, proposed a form of counter magic. She told Tituba to bake

a rye cake with the urine of the afflicted victim and feed the cake to a dog.

( Dogs were believed to be used by witches as agents to carry out their devilish

commands.) By this time, suspicion had already begun to focus on Tituba, who had

been known to tell the girls tales of omens, voodoo, and witchcraft from her native

folklore. Her participation in the urine cake episode made her an even more obvious

scapegoat for the inexplicable.

Meanwhile, the number of

girls afflicted continued to grow, rising to seven with the addition of Ann Putnam,

Elizabeth Hubbard, Susannah Sheldon, and Mary Warren. According to historian Peter

Hoffer, the girls "turned themselves from a circle of friends into a gang

of juvenile delinquents." (Many people of the period complained that young

people lacked the piety and sense of purpose of the founders' generation.) The

girls contorted into grotesque poses, fell down into frozen postures, and complained

of biting and pinching sensations. In a village where everyone believed that the

devil was real, close at hand, and acted in the real world, the suspected affliction

of the girls became an obsession.

Sometime after February

25, when Tituba baked the witch cake, and February 29, when arrest warrants were

issued against Tituba and two other women, Betty Parris and Abigail Williams named

their afflictors and the witchhunt began. The consistency of the two girls' accusations

suggests strongly that the girls worked out their stories together. Soon Ann Putnam

and Mercy Lewis were also reporting seeing "witches flying through the winter

mist." The prominent Putnam family supported the girls' accusations, putting

considerable impetus behind the prosecutions.

Once diagnosed

as victims of witchcraft, the girls were asked to identify their tormentors. Ann

pointed fingers at Sarah Good and Sarah Osburne. She was also quick to testify

against Tituba, claiming an apparition of the West Indian woman had “tortured

me most grievously by pricking and pinching me most dreadfully.”

Tituba

was an obvious choice. Parris was enraged when he found out about the 'witchcake',

and beat her until she confessed to being a witch. Good was a beggar and social

misfit who lived wherever someone would house her, and Osborn was old, quarrelsome,

and had not attended church for over a year. The Putnams brought their complaint

against the three women to county magistrates Jonathan Corwin and John Hathorne,

who scheduled examinations for the suspected witches for March 1, 1692 in Ingersoll's

tavern. When hundreds showed up, the examinations were moved to the meeting house.

At

the examinations, the girls described attacks by the specters of the three women,

and fell into their by then perfected pattern of contortions when in the presence

of one of the suspects. Other villagers came forward to offer stories of cheese

and butter mysteriously gone bad or animals born with deformities after visits

by one of the suspects.The magistrates, in the common practice of the time, asked

the same questions of each suspect over and over: Were they witches? Had they

seen Satan? How, if they are were not witches, did they explain the contortions

seemingly caused by their presence? The style and form of the questions indicates

that the magistrates thought the women guilty.

The matter

might have ended with admonishments were it not for Tituba. After first adamantly

denying any guilt, afraid perhaps of being made a scapegoat, Tituba claimed that

she was approached by a tall man from Boston--obviously Satan--who sometimes appeared

as a dog or a hog and who asked her to sign in his book and to do his work. Yes,

Tituba declared, she was a witch, and moreover she and four other witches, including

Good and Osborn, had flown through the air on their poles. She had tried to run

to Reverend Parris for counsel, she said, but the devil had blocked her path.

Tituba's confession succeeded in transforming her from a possible scapegoat to

a central figure in the expanding prosecutions. Her confession also served to

silence most skeptics, and Parris and other local ministers began witch hunting

with zeal.

Soon, according to their own reports, the spectral

forms of other women began attacking the afflicted girls. Martha Corey, Rebecca

Nurse, Sarah Cloyce, and Mary Easty were accused of witchcraft. During a March

20 church service, Ann Putnam suddenly shouted, "Look where Goodwife Cloyce

sits on the beam suckling her yellow bird between her fingers!" Soon Ann's

mother, Ann Putnam, Sr., would join the accusers. Dorcas Good, four-year-old daughter

of Sarah Good, became the first child to be accused of witchcraft when three of

the girls complained that they were bitten by the specter of Dorcas. (The four-year-old

was arrested, kept in jail for eight months, watched her mother get carried off

to the gallows, and would "cry her heart out, and go insane.") The girls

accusations and their ever more polished performances, including the new act of

being struck dumb, played to large and believing audiences.

Stuck

in jail with the damning testimony of the afflicted girls widely accepted, suspects

began to see confession as a way to avoid the gallows. Deliverance Hobbs became

the second witch to confess, admitting to pinching three of the girls at the Devil's

command and flying on a pole to attend a witches' Sabbath in an open field. Jails

approached capacity and the colony "teetered on the brink of chaos"

when Governor Phips returned from England. Fast action, he decided, was required.

Phips

created a new court, the "court of oyer and terminer," to hear the witchcraft

cases. Five judges, including three close friends of Cotton Mather, were appointed

to the court. Chief Justice, and most influential member of the court, was a gung-ho

witch hunter named William Stoughton. Mather urged Stoughton and the other judges

to credit confessions and admit "spectral evidence" (testimony by afflicted

persons that they had been visited by a suspect's specter). Ministers were looked

to for guidance by the judges, who were generally without legal training, on matters

pertaining to witchcraft.

Mather's advice was heeded. the

judges also decided to allow the so-called "touching test" (defendants

were asked to touch afflicted persons to see if their touch, as was generally

assumed of the touch of witches, would stop their contortions) and examination

of the bodies of accused for evidence of "witches' marks" (moles or

the like upon which a witch's familiar might suck).

Evidence

that would be excluded from modern courtrooms-- hearsay, gossip, stories, unsupported

assertions, surmises-- was also generally admitted. Many protections that modern

defendants take for granted were lacking in Salem: accused witches had no legal

counsel, could not have witnesses testify under oath on their behalf, and had

no formal avenues of appeal. Defendants could, however, speak for themselves,

produce evidence, and cross-examine their accusers. The degree to which defendants

in Salem were able to take advantage of their modest protections varied considerably,

depending on their own acuteness and their influence in the community.

On

18 April 1692 Exekiell Chevers and John Putnam, Jr. made a complaint against Giles

Corey for witchcraft done on Ann Putnam, Marcy Lewis, Abig'l Williams, Mary Walcot

and Eliz. Hubert. At his trial, the court ordered Cory's hands to be tied, and

they asked him if it were not enough to "act witchcraft at other times, but

must you do it now in face of authority?" He replied, "I am a poor creature

and cannot help it." Again, a magistrate exclaimed, "Why do you tell

such wicked lies against witnesses?" One of his hands was loosed and the

girls were afflicted. He held his head on on side, and the heads of the afflicted

were held on one side. He drew in his cheeks, and the cheeks of the afflicted

were sucked in.

Displeased with the course of the case, Thomas

Putnam wrote a letter to Judge Samuel Sewall in which he brought up an old case

against Giles Corey:

| "...my daughter Ann...there appeared unto her (she said) a man in a Winding Sheet; who told her that Giles Cory had Murdered him, by Pressing him to Death with his Feet; but that the Devil there appeared unto him, and Covenented with him, and promised him, He should not be Hanged....For all people now Remember very well, (and the Records of the Court also mention it,) That about Seventeen Years ago, Giles Cory kept a man in his House, that was almost a Natural Fool: which Man Dy'd suddenly. A Jury was Impannel'd upon him, among whom was Dr. Zorobbabel Endicot; who found the man bruised to Death, and having clodders of Blood about his Heart. The Jury, whereof several are yet alive, brought in the man Murdered; but as if some Enchantment had hindred the Prosecution of the Matter, the Court Proceeded not against Giles Cory, tho' it cost him a great deal of Money to get off." |

He

was asked to plead, that is, to appeal to his country, to a jury trial, which

at that time all persons charged with crime must do before a jury could try them.

He "stood mute," and would not plead. The old English Law of "Peine

forte et dure" furnished but one remedy for this situation. The prisoner

should: "be remanded to the prison from whence he came and put into a low

dark chamber, and there be laid on his back on the bare floor, naked, unless when

decency forbids; that there be placed upon his body as great a weight as he could

bear, and more, that he hath no sustenance, save only on the first day, three

morsels of the worst bread, and the second day three droughts of standing water,

that should be alternately his daily diet till he died, or, till he answered.

Giles

Cory suffered this rather than to appeal to his countrymen, as he was fully convinced

that he must die anyway, and he was obstinate enough to cheat the gallows. So

to avoid giving the prosecution any advantage, he would answer nothing, whereupon

he was sentenced to be pressed to death. Giles reportedly was a stubborn, fiery

man who realized that he would not get a fair trial. By not pleading one way or

the other, English law dictated that a person could not be tried, but the penalty

for standing mute was "slow crushing under weights" until a plea was

forthcoming or the person died.

On September 17, the Sheriff

led Giles to a pit in the open field beside the jail and before the Court and

witnesses in accordance with an English procedure of the "Peine forte et

dure". They stripped Giles of his clothing, laid him on the ground in the

pit, placed boards on his chest, six men lifted heavy stones, placing them one

by one, on his stomach and chest. Giles Corey did not cry out, which perplexed

Sheriff Corwin whose duty it was to squeeze a confession from the old man.

After

two days, Giles was asked three times to plead innocent or guilty to witchcraft,

to which he would say more weight. "Do you confess?" the Sheriff cried

over and over. More and more rocks were piled onto him, and the Sheriff, from

time to time, would stand on the boulders staring down at Corey's bulging eyes.

Robert Calef, who was a witness along with other townsfolk, later said, "In

the pressing, Giles Corey's tongue was pressed out of his mouth; the Sheriff,

with his cane, forced it in again."

Three mouthfuls

of bread and water were fed to the old man during his many hours of pain. Finally,

Giles Corey cried out at Sheriff Corwin, "Damn you. I curse you and Salem!"

Giles Corey died a few seconds later.

The day following Cory's

death, Thomas Putnam sent to Judge Sewall the following communication:

| "Last night my daughter Ann was grievously tormented by witches, threatening that she should be pressed to death before Giles Corey, but through the goodness of a gracious God, she had, at last, a little respite. Whereupon there appeared unto her (she said) a man in a winding sheet who told her that Giles Corey had murdered by pressing him to death with his feet; but that the devil then appeared unto him and covenanted with him and promised him that he should not be hanged. The apparition said, God hardened his heart that he should not hearken to the advice of the court, and so die an easy death; because, as it said, it must be done to him as he had done to me. The apparition also said that Giles Corey was carried to the court for this and that the jury had found the murder; and that her father knew the man and the thing was done before she was born." |

But the Putnams didn't stop there: Rebecca (Towne) Nurse was, along with 18 others

who were tried by an illegal court, heinously murdered by hanging. There were

several reasons why she was targeted. The first reason was her relationship to

a prominent citizen of the town of Topsfield, Francis Nurse, her husband. The

town of Topsfield had for some time been in dispute over land along the boarder

of Salem Village. That is to say the Putnam family estate.

Second, was her affiliation with the church in Salem Town. She was a member of

the church in Salem Town and her husband was an outspoken leader of the anti-Parris

committee. This was a committee who believed the reverend Parris was not hired

properly and should be removed from the position of minister for the church of

Salem Village. Again, the Putnams were the leaders of the pro-Parris committee.

Third, this may have been a test for the Putnams. If they could bring down such

a highly respected, deeply religious, pious pillar of the community, then surely

they'd have absolute freedom over those they'd bring charges against in the future.

Also, Rebecca's two sisters were also accused for many of the same reasons. Several

years earlier Rebecca's mother was accused of witchcraft. She was, however, never

tried. Local gossip during the trials suggested the profession was passed down

from mother to daughters.

Rebecca was 70 years old when

the Court of Oyer and Terminar (Hear and Determine) tried her. Governor Phipps

formed the court at the request of the Lieutenant Governor, William Stoughton.

Stoughton was then assigned by Phipps to serve as Chief Magistrate. It should

be noted that only the Judicial Branch of the Provincial Government could form

a court as a part of governmental checks and balances. Clearly, Phipps was overstepping

his own authority. Additionally, none of the magistrates of the Court of Oyer

and Terminar had any legal training and relied heavily on their various religious

backgrounds.

The trial itself was a sham and a virtual mockery

of the judicial system. Edward and Jonathan Putnam signed the complaint. The charge

was for afflicting Ann Putnam Jr. and Abigail Williams. Ann Putnam, Sr. testified

that the ghosts of Benjamin Houlton, Rebecca Houlton, John Fuller, and her sister

Baker's children (6 of them) as well as her sister Bayley and her three children

came to her at various times in their winding sheets and cried for justice of

being murdered by Rebecca Nurse. John Putnam, Sr. and his wife Rebecca (Prince)

Putnam actually refuted charges that Rebecca Nurse had murdered their daughter

Rebecca Shepard and their son-in-law John Fuller. Sarah Nurse (Rebecca's daughter)

testified she saw Goodwife Bibber (an afflicted woman in the trial) pull pins

out of her clothes and hold them between her fingers, and clasp her hands around

her knees, and then she cried out and said, "Goody Nurse pricked me."

On June 2, 1692, two physical exams to search for witch's marks were performed

by midives. On June 28, 1692, Rebecca petitioned the court for another physical

exam citing one previous examiner to be of contradictory opinion from the others.

At her trial, testimonials regarding her Christian behavior, care, and education

of her children brought a verdict of not guilty. William Stoughton then politely

asked the jury to again retire and reconsider their verdict. So much for not being

tried twice for the same

Now this legal charade—lawful

murder—had been taken so far that even the family patriarch and matriarch

couldn't stop it: A petition was drawn and signed—even by John Sr. and his

wife—to save Rebecca. She was granted a temporary reprieve by Governor Phipps,

but finally hanged on July 19, 1692.

Meanwhile,

George Burroughs had moved his ministry to a church in Maine, this time in a small

town named Wells, where he probably heard rumors of the chaos in Salem and thanked

God he wasn't living there anymore. Like Casco once had been, Wells was always

under the threat of Indian attack. During this time, Burroughs wrote two letters

of petition to officials in Boston, pleading for protection from the hostile neighbors.

His letters received little attention, however, because his Indian problems were

insignificant when compared to the presence of something much larger - Thomas

Putnam, Jr., and brother-in-law Jonathan Walcott made the cry of witchcraft against

him. Both men saw George Burroughs as an enemy of their family.

In

a written statement, Thomas Putnam accused George Burroughs of witchcraft. Putnam

had written a letter, both "unctuous and melodramatic," to John Hathorne

and Jonathan Corwin, magistrates, in an effort to warn them of the developing

case against George Burroughs:

| "Much honored: After most humble and hearty thanks presented to your honors for the great care and pains you have already taken for us, for which we are never able to make you recompense...and we, beholding continually the tremendous works of divine providence - not only everyday but every hour - thought it our duty to inform your Honors of what we conceive you have not heard, which are high and dreadful: of a wheel within a wheel, at which our ears do tingle. Humbly craving continually your prayers and help in this distressed case, so praying almighty God continually prepare you, that you may be a terror to evil-doers and a praise to them that do well, we remain yours to serve in what we are able." |

In

this letter, the manipulative nature of Thomas Putnam is evident. His lack of

detail exhibits the power Putnam wished to believe he had. He assumed the magistrates

would be intrigued by the "tingling of his ears," and rush to him for

his knowledge and assistance. "His tone is reminiscent of that of the Shakespearean

character often considered the embodiment of evil. Iago’s wicked plotting,

often thought to be motiveless, was in fact based on sexual and political envy

and fury...It seems a reasonable assumption that Thomas was not unlike Iago in

his vengefulness, given the great number of his complaints against accused witches

and....depositions testifying to their crimes." Putnam, like Iago from Othello,

genuinely detested those who had ever crossed him. His daughter, Ann Putnam, Jr.,

was to be one of the most powerful accusers during the witch trials. Her testimonies

against George Burroughs were among the "strangest and gruesome" of

the trials, and perhaps the most damaging. Her father’s hatred of Burroughs

was evident in the words of Ann’s accusations.

Historian

Frances Hill believes that Ann Putnam was encouraged to speak especially harsh

about George Burroughs by her father. Her parents had little affection for Burroughs,

and it seems that they displayed their hatred openly in front of Ann. She would

have known little information about Burroughs, such as his time in Casco, or the

death of his wives, had her parents not filled her head with such knowledge. The

stories told about him and his abusive nature would have scared a young girl.

The terms which her parents used to describe this man whom they detested surely

would have frightened Ann enough to the point where she, too, would believe that

he was inherently evil. The encouragement of her parents definitely heightened

her proclivity towards crying out against Burroughs. "A mixture of guile

and manipulation and self-delusion seems more probable than sheer conscious fraud.

It is true that if any one person involved in the witch-hunt was utterly cynical

and unscrupulous, that person was [Thomas] Putnam."

Ann

Putnam’s most terrifying vision during the hysteria came just the day before

her father wrote to the magistrates of the forthcoming madness. "She had

seen the apparition of a minister of God who tortured her and tried to force her

to write in his book. When she asked him his name he told her that it was George

Burroughs…he was ‘above a witch for he was a conjurer.’" With

this testimony, Ann Putnam declared George Burroughs to be not only a witch, but

also the leader of the witches.

Many accusers swore that

Burroughs was the spiritual leader of all the New England witches, having been

promised by Satan that he would one day be the King of Hell. Deliverance Hobbs

proved to be the most agreeable witness of all the accused witches. She spoke

freely; painting details that pleased the magistrates and the spectators. Her

most descriptive testimonies declared George Burroughs the leaders of the witch’s

coven in New England.

The statement Deliverance made was

perfect for silencing doubters and confirming everyone else’s worst fears.

She claimed there was a witches’ church in Salem Village that held meetings

that were black next to Mr. Parris’s house. There were deacons, who gave

out red bread and red wine, and a preacher who administered the sacrament. That

preacher was an especially sinister figure…The minister urged his followers

to bewitch everyone in the village, ‘telling them that they should do it

gradually, not all and once [and] assuring them that should prevail.’ The

deacons were Rebecca Nurse and Sarah Wildes. The minister was George Burroughs.

It

was claimed that the either Burroughs, or, sometimes, the Devil himself, presided

over such meetings. The confessors believed the mock sacrament was to serve as

the beginning of a sermon from Satan. "Confessed witches would later testify

that he baptized converts to the Devil and led [the] satanic masses in the dark

woods."

After hearing testimonies such as these, a warrant

was set for the arrest of Burroughs, and Marshall John Partridge went to serve

it, though he refused to go alone out of fear. Arriving in Wells during the Sunday

morning worship, the men forced Burroughs to leave with them before the services

were completed. Partridge and his men were afraid of Burroughs from the outset

of their journey, and were convinced that Burroughs, invoking the aid of Satan

in an effort to break free, caused a thunderstorm on their return to Salem. After

his arrival in Salem on May 4, 1692, George Burroughs did not receive examination

before the council of Magistrates until five days later.

At

the first examination, a group of men consisting of Deputy-Governor William Stoughton,

William Sewall, Jonathan Corwin, and John Hathorne questioned Burroughs. The questions

posed were more of a religious rather than legal nature. For example, when asked

how long it had been since he had partaken of the Sacrament. His answer shocked

the examiners, because "it was so long since he could not tell: yet he owned

he was at meeting on Sab: at Boston part of the day, and the other a [t] Charlestown

part of a Sab: when that sacrament happened to be at both, yet he did not partake

of either." Also of interest to the examiners was the status of baptism of

his children, because only the eldest had received the sacrament. The examiners

also brought in evidence about the home of Burroughs in Casco, that toads had

overrun it. "The absurdity of this admission fades only slightly on remembering

that a toad in Puritan eyes was a sinister creature, perhaps one of Satan’s

minions, perhaps Satan himself."

After the private inquiry,

the Magistrates brought Burroughs before the meeting house so that he could be

examined publicly. Many of the girls were taken with seizures when he entered

the room, dropping to the floor as though in great pain. Susannah Sheldon was

one of the first girls to cry out against Burroughs after Ann Putnam, and her

deposition read:

| "Mr. Burros which brought a book to me and told me if I would not set my hand to it he would tear me to pieces. I told him I would not, then he told me he would starve me to death. Then the next morning he told me he could not starve me to death, but he would choke me to death, that my vittles should do me but little good. Then he told me his name was Borros, which had preached at the village. The last night he came to me and asked me whether I would go to the village tomorrow to witness against him. I asked him if he was examined then. He told [me] he was. Then I told him I would go. Then he told me he would kill me before morning. Then he appeared to me at the house of Nathaniel Ingolson and told me he had been the death of three children at the eastward and had killed two of his wives, the first he smothered and the second he choked, and killed two of his own children." |

After

Susannah finished reading her statement, the court ordered Burroughs to look directly

at her, at which point she, and all the other girls present, fell to the ground.

Several began to scream that he had bitten them to discourage them from speaking

out against him, showing the teeth marks on the arms to prove their accusations.

"It was Remarkable that wheras Biting was one of the ways that the Witches

used for the vexing of the Sufferers, when they cry’s out of G.B. biting

them, the print of the Teeth would be seen on the Flesh of the Complainers, and

just such a sett of teeth as G.B.’s would then appear upon them, which could

be distinguished from those of some other mens." The Magistrates forced Burroughs

to open his mouth, to prove that he had teeth, as many of those accused of the

same actions did not have teeth with which to bite.

The circumstances

surrounding the deaths of George Burroughs’ wives would become serious accusations

that evolved into some of the strongest evidence against the minister. There was

testimony that the ghosts of Burroughs’ wives appeared to them as a warning.

The Putnam family spoke out the loudest against Burroughs.

The

Deposition of John Putnam and Rebecca his Wife:

| "Testifieth and saith, that, in the year 1680, Mr. Burroughs lived in our house nine months. There being a great difference betwixt said Burroughs and his wife, the difference was so great that they did desire us, the deponents, to come into their room to hear their difference. The controversy that was betwixt them was, that the aforesaid Burroughs did require his wife to give him a written covenant, under her hand and seal, that she would never reveal his secrets. Our answer was, that they had once made a covenant we did conceive did bind each other to keep their lawful secrets. And further saith, all the time that Burroughs did live at our house, he was a very harsh and sharp man to his wife; notwithstanding, to our observation, she was a good and dutiful wife to him." |

Other

than the Putnam family, others spoke out against the treatment of the wives of

Burroughs during their lifetimes. There were testimonies that alleged he had knowingly

kept his ill wife outside, forbade contact with their families, and had kept "his

two successive wives in a strange kind of slavery."

The

spousal abuse, according to the accusers and the afflicted girls, turned to murder.

Susannah Sheldon, Mary Walcott, Mercy Lewis, Abigail Williams, and Ann Putnam,

Jr. all swore before the Magistrates that the ghosts of Burroughs’ wives

appeared to them. Despite their testimony that the murders did occur, there was

no one cohesive version that the girls told the court. For example, Susannah Sheldon

claimed Burroughs smothered and the choked the second. Mary Walcott said that

his first wife died while giving birth, because she allowed only in the drafty

kitchen. Not surprisingly, it was the testimony of Ann Putnam that was both the

most detailed and damning. She testified the ghosts of the two women appeared

to her and "... turned their faces towards Mr. Burroughs and looked very

red and angry and told him that he had been a cruel man to them and that their

blood did cry for vengeance against him and also told him that they should be

clothed in white robes in heaven, when he should be cast into hell." After

the disappearance of Burroughs, the women proceeded to tell Ann a detailed account

of their respective murders. The first wife said Burroughs had stabbed her, the

wound never discovered because Burroughs had placed sealing wax upon it immediately

after her death. The second told Ann that she was killed en route to visit her

friends, assisted by Burroughs’ current wife.

Mercy

Lewis, another of the afflicted girls, was under the employment of Thomas Putnam,

and lived in his house with his family. That she lived with Putnam is important,

because she experienced his tirades against Burroughs, as did his daughter Ann.

Mercy had been in the household of George Burroughs as well, when in 1689, her

parents were lost in an Indian raid on Falmouth. Burroughs had taken her in initially,

and "shortly thereafter, she came to live with the Sergeant Thomas Putnam…Putnam

clan leaders Thomas Putnam and Jonathan Walcott bought complaint against Burroughs

on April 30, 1692, for witchcraft. Mercy Lewis was one of his supposed victims,

and she joined her name to the list of complainants."

When

Lewis read her statement, she felt such pains that she had to take leave of the

meeting house before she could return and testify. In her absence, Burroughs said

that he could not understand what was happening around him. When asked who he

thought was responsible for the accusations of the girls, he answered that he

could not possibly know. Burroughs said he assumed that it was the devil. He said,

"when they begin to name my name, they cannot name it." This was perhaps

a suggestion on his part that the girls were accusing the wrong man.

Mercy

Lewis claimed that Satan had appeared to her and offered her "gold and many

fine things" if she would sign the book. A few weeks after this experience,

Satan again appeared to her, this time in the form of George Burroughs. Mercy

Lewis said that "Mr. Burroughs carried me up to an exceedingly high mountain

and showed me all the kingdoms of the earth, and told me that he would give them

all to me if I would write in his book." Abigail Williams and Elizabeth Parris

also said that they were promised fine gifts if they were to accept the rule of

Satan.

After more testimony of this sort, the Magistrates

ordered George Burroughs taken to jail to await the beginning of his trial. During

his time in jail, the Grand Jury handed down four indictments, one saying:

| Anno

Regis et Regina, etc..., quarto. Essex, ss. The jurors of our Sovereign Lord and Lady, the King and Queen, present, that George Burroughs, late of Formuth in the Province of Massachusetts Bay, the ninth day of May in the fourth year of the reign of our Sovereign Lord and Lady, William and Mary, by the Grace of God, of England, Scotland, France, and Ireland, King and Queen, defenders of the faith, etc., and divers other days and times as well before as after, certain detestable acts, called witchcraft and sorceries, wickedly and feloniously hath used, practiced, and exercised at and within the town of Salem in the County of Essex, aforesaid, in, upon, and against Mary Walcott, of Salem Village in the County of Essex, single woman; by the which said wicked acts the said Mary Walcott, the ninth day in the fourth year aforesaid, and divers other days and times, as well as before as after, was and is tortured, afflicted, pined, consumed, wasted, and tormented, against the peace of our Sovereign Lord and Lady, the King and Queen, and against the force of the statute in that case made and provided. |

By

the time of his trial on August 5, there were more than thirty depositions written

against Burroughs, most of them calling on spectral evidence of the accused girls

and "his…supernatural strength and his ability to hear conversations

when he was not present." When he was brought to the courtroom to face the

Court of Oyer and Terminer, there was a large crowd gathered, for it was Burroughs

who was rumored to be the "ringleader" of the witches. Because of the

tremendous amount of "evidence" against him, Burroughs sought to convince

the court that there was no witch cult. Burroughs made a dangerous admission,

saying, "signing a compact with the Devil did not enable a Devil to torment

other people at a distance." Burroughs took this argument from a seventeenth-century

skeptic, Thomas Ady, who wrote in A Candle in the Dark: "The grand error

of these latter ages is ascribing power to witches, and by foolish imagination

of men’s brains, without grounds by the scriptures, wrongful killings of

the innocent under the name of witches." The judges, however, were not willing

to let the ringleader escape death.

George Burroughs faced

death for the crime of witchcraft. Many see his conviction, as well as others

given the same sentence, as ludicrous because it was decided upon due to spectral

evidence. This is evidence given in the testimonies which claimed that spirits

of the accused would torment the young afflicted, often biting or scratching their

arms and legs. It is interesting to note that the most outspoken opposition to

the use of such evidence was the minister Cotton Mather, who wished the trials

to be over as soon as possible, and by any means necessary. It would seem that

Mather would favor spectral evidence, because it was the quickest means of purifying

the village from the wrath of Satan. Yet, he implored the judicial board, led

by John Richards, to be wise in their administration of the trials, especially

where spectral evidence was concerned.

| "And yet I must most humbly beg you that in the management of the affair in your most worthy hands, you do not lay more stress upon pure specter testimony than it will bear. When you are satisfied or have good plain legal evidence that the Demons which molest our poor neighbors do indeed represent such and such people to the sufferers, though this be a presumption, yet I suppose you will not reckon it a conviction that the people so represented are witched to be immediately exterminated. It is very certain that the Devils have sometimes represented the shapes of persons not only innocent but very virtuous, though I believe that the just God then ordinarily provides a way for the speedy vindication of the persons thus abused…Perhaps there are wise and good men that may be ready to style him that shall advance this caution a witch advocate, but in the winding up this caution will certainly be wished for." |

|

Mr. Burroughs was carried in a cart with the others through the streets of Salem to execution. When he was upon the ladder he made a speech for the clearing of his innocency, with such solemn and serious expressions as were to the admiration of all present. His prayer (which he concluded by repeating the Lord’s prayer) was so well worded, and uttered with such composedness, and such (at least seeming) fervency of spirit as was very affecting and drew tears from many (so that it seemed to some that the spectators would hinder the execution).

This completion of the Lord’s prayer was a feat in the eyes of many, because it was widely believed that men of the devil could not say the prayer because of their evil allegiance. Immediately affected by this, some in the crowd began demanding that the execution be stopped. The afflicted girls, however, shouted that "The Black Man" had been prompting Burroughs during his prayers. Cotton Mather stepped forward, proclaiming that "Burroughs was no ordained minister" and that "the Devil has often been transformed into an angel of light."

By the time the witch hunt was over, Ann had accused 62 people. In the coming years, she would have a difficult life. Both her parents died, leaving her to raise her nine brothers and sisters on her own. But she did something none of the other circle girls would do—publicly acknowledge her role in the trials. In 1706 she stood before the church as the pastor read her apology.

In the spring of 1693, Sir William Phips, Governor of Massachusetts, liberated 168 people in Salem's Witch Dungeon who awaiting the hangman's noose. Several of these people died shortly thereafter from their neglect and abuse while in the dungeon. By 1710, the General Court had begun to "reverse some of the convictions, judgments and attainders and declare them null and void," and in the next year or two some compensation, if inadequate, had been paid to the families of some of the sufferers. The First Church in Salem erased from their records and blotted out the excommunication of Rebecca Nurse and Giles Cory.

The Reverend Samuel Parris, after a long acrimonious struggle with the men whose wives, mothers, and friends he had helped to drag to the gallows, was driven from the Village in 1697, and, after unimportant service in the frontier towns, died in Sudbury in 1720. His wife died and was buried in Danvers before he left that parish.

So as you can see, John Putman was not a good man. Whether he was truly evil, misguided, or just incredibly naive is anyone's guess. Of course, it doesn't mean that his children were evil. After all, we're related to one of them:

CHILDREN OF JOHN PUTNAM II AND REBECCA PRINCE |

PRISCILLA

PUTNAM was born on the 4th of March, 1657, in Salem, Essex, Massachusetts. Priscilla

married Joseph BAILEY, son of John Bailey and Eleanor

Emery, in 1675 in Newbury, Essex, Massachusetts. Joseph was born on 14 Apr

1648 in Newbury, Essex, Massachusetts. He died on 23 Oct 1723 in Arundel, Lincoln,

Massachusetts. She died on the 16th of November in 1704.

The

children

of Priscilla Putnam and Joseph Bailey are:

CHILDREN OF PRISCILLA PUTNAM AND JOSEPH BAILEY |

GENEALOGY

RICHARD PUTNAM (ABT. 1490 - 1556-7) married JOAN and begat...

JOHN PUTNAM (d. 1573) who married MARGERY and begat...

NICHOLAS PUTNAM who married MARGARET GOODSPEED and begat...

JOHN PUTNAM (1579 - ) who married PRISCILLA GOULD and begat...

JOHN PUTNAM II, who married REBECCA PRINCE and begat...

PRISCILLA PUTNAM (b.1657), who married JOSEPH BAILEY and begat...

SARAH BAILEY, who married ISRAEL JOSLIN (1693 - 1761) and begat...

SARAH JOSLIN (b. 1722), who married JOSEPH MUNYAN (1712

- 1797) and begat...

JOSEPH MUNYAN (d. 1831), who married MARY

MARSH (1750 - 1820) and begat...

AMASA MUNYAN (b. 1800), who married

SUSANNA HENNING (1802 - 1821) and begat...

MARY ANN MUNYON (1823 - 1899) married WILLIAM POTTER (1819 - 1894) and begat...

LOUISA EDITH POTTER (1856 - 1891) who married ABRAHAM CANE WINTERS (1829 - 1893) and begat...

NELLE WINTERS (1885 - 1974) who married WILLIAM PRITCHARD (1880 - 1958) and begat...

DOROTHY PRITCHARD (b. 1918) who married ERWIN WENK (1910 - 1982) and begat...

MARTHA WENK (b. 1940) who married CARLETON MARCHANT HAUSE, JR. (b. 1939) and begat...

JEFF (who married LORI ANN DOTSON), KATHY (who married HAL LARSEN), ERIC (who married MARY MOONSAMMY), and MICHELE HAUSE (who married JOHN SCOTT HOUSTON).

Puttenham

Coat of Arms 1400

Quaere an sit caput vulpis vel damae

Don't

mistake this fox's head for that of a deer.

SOURCES

FHL film #2972

Erikson, Kai T. "Witchraft and Social Disruption," Mappen, Marc, Ed. Witches and Historians: Interpretations of Salem. (Malabar, FL: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company, 1980), 107.

.gif)