"One German makes a philosopher, two a public meeting, three a war."

—Robert D. MacDonald.

|

But the key figure for us in this story is not actually Frederick, but his wife, Elizabeth. (In fact if you believe family legend, we're related to her.) Elizabeth was the daughter of King James I of England, and part of the Stuart dynasty. She was said to be incredibly beautiful, and had attracted most of the royal suitors of Europe before (and after) her marriage. In fact, she was nicknamed the “Queen of Hearts.” But she eventually married Frederick V in 1613, in order to cement an alliance between English and German Protestantism (detailed here in the Stuart Genealogy).

But to understand our family's connection to Elizabeth, we need to first learn the story of Amalia of Solms-Braunfels (31 August 1602 - 8 September 1675). She was the daughter of Grafen (Duke) Johann Albrecht I of Solms-Braunfels (1563-1623) and his first wife, Countess Agnes of Sayn-Wittgenstein (1569-1617). They were cousins, with their paternal grandparents being Conrad Graf zu Solms-Braunfels and Countess Elisabeth of Nassau-Dillenburg. Amalia spent her childhood at the parental castle at Braunfels. But in the summer of 1619, Amalia of Solms-Braunfels went to the Heidelberg court and became part of the train ( a "lady in waiting") of Elizabeth. Eventually, through Elizabeth, she would rule Nassau and then bear a son who would rule England. (But more on that later.)

When Ferdinand II heard that Frederick had been elected ruler of Bohemia, he refused to recognize the new "king" and sent two Catholic "councilors" (Martinitz and Slavata) to Hradcany castle in Prague to make way for his coronation as the rightful heir to the throne. But the Bohemian Calvinists seized the councilors and threw them out of a palace window. (The official Catholic version of the story claims that angels suddenly appeared and carried them to safety. The official Protestant version says that they landed in manure.)

This event, known as the second defenestration of Prague, began the "Bohemian Revolt" which erupted in Bohemia, Silesia, Lusatia and Moravia.

|

|

So now Frederick was battling Spain, as well. Worse yet, his most powerful political ally, his father-in-law King James of England, ignored his pleas for help against the Spanish. Why? Because James cared more about land and political alliances than family, and was actually supporting the Spanish, over his own daughter, Elizabeth! (I hope he wasn't expecting a nice gift on Father's Day.)

Frederick's allies in the Union saw the cause as lost and abandoned him. So his brief reign as the King of Bohemia ended with his defeat at the Battle of White Mountain (8 November 1620)—only two months after his coronation—and earned him the derisive nickname of 'the Winter King'.

In the spring of 1621, Frederick V was forced to flee and lived the rest of his life in exile with his wife and family at the Hague. Lady in Waiting Amalia of Solms-Braunfels fled with the pregnant queen to the west. Shelter was denied to them because the emperor forbade it. Elizabeth went into labour during their flight and Amalia helped her with her delivery. The end of their journey was the Hague, where Stadtholder Maurice of Nassau gave them asylum in 1621.

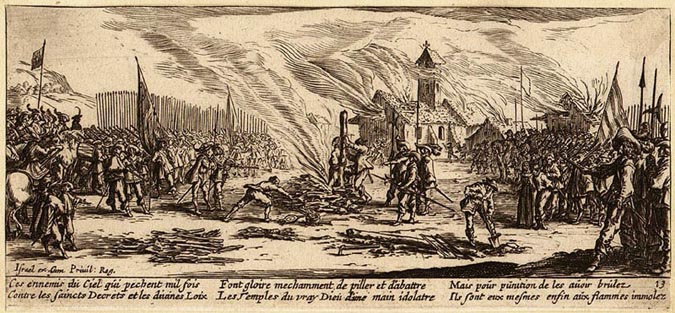

The catastrophic defeat of the Protestant army at White Mountain meant that eastern Germany was up for grabs. The Spanish took the Rhine Palatinate, seeking to outflank the Dutch in preparation for the soon-to-be-renewed Eighty Years' War. Before the end of that war, France, several German states, Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands also fought their way through the land. The area was looted and pillaged, remade, then looted and pillaged again, by different invaders for many years.

|

|

Elizabeth Stuart, daughter of England's James I, mourning for her husband, Elector Palatine Frederick V. (By Gerard Honthorst, @1634.) |

Finally in 1648, the second Teutsche Krieg ended with a truce, aimed at balancing the powers of the European nations. The Netherlands and Spain lost their predominance to France. The idea of a Catholic empire under Pope and emperor was abandoned, and a community of sovereign states was established instead. Protestantism was given equal voice with Catholicism. The word "Holy" was removed from the title of the German emperor; he became a feudal overlord rather than a monarch.

The major outcome of the war was that the rich got richer, and the poor—who couldn't get any poorer—got screwed again: Over 300 princelings, bishops, abbots and rulers of free cities retained the right to levy taxes, to field armies (just not against the emperor), to make internal laws and to enter into treaties with whomsoever they chose. In other words, the German people who were lucky enough to survive the worst war in their history were about to be exploited even worse.

The country's land was devastated, and many villages had been looted and burned to the ground. The war had destroyed Germany's capital resources and its living standards fell... Not that there were many people left to work the land, anyway.

During this conflict, over 300,000 German soldiers had died in battle. Millions of citizens had died of malnutrition and disease. Most authorities say that the population of the German empire dropped from about 21,000,000 to 13,500,000 between 1618 and 1648, meaning one out of every three people had died, more than in all later wars combined (including World War I and World War II). The Hessian territory around Marburg lost more than two thirds of its population, thanks to the local "Dreissigjaehrigen" war of 1645-1648 (a sub-conflict of the Thirty Years' War in which Hessen-Kassel and Hessen-Darmstadt again fought over the Marburg territory).

|

|

"The first John Hause was born in Germany in the year 1690, and when an infant, on account of Religious Persecutions, he was transported by his "cousin", Queen Mary ll, of Great Britian, House of Stuart, Daughter of James l l and Anne Hyde, born 1662, married William, Prince of Orange at the age of 17, reigning 15 years, and died in 1694 of Small Pox, leaving no children. A kind, meek. and noble Queen"

—From records copied in the Bible of Joseph Hause of Ovid, New York.

|

Then in 1624, Prince Maurice of Nassau was on his deathbed, and he made his half-brother Frederik promise to marry—and so to fulfill Maurice's dying wish, Frederik finally wed Amalia of Solms-Braunfels on 4 April 1625.

Frederik then became the stadtholder, and his influence grew substantially—as did Amalia's. Together they succeeded in expanding court life in the Hague, making it a center of the arts. They also expanded their worldwide influence by arranging politically-advantagious marriages for their children. Most notably, Amalia arranged the marriage of their son, William II, to the niece of her old boss, Elizabeth the Queen of Hearts: The bride was Princess Mary—and she was the eldest daughter of none other than King Charles I of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

This marriage would tie the Dukes of Solms to the British Empire—especially after William and Mary's son, William III, married his first cousin, Mary II, and they went on to become the King and Queen of all England. Their crowning made the Graf (Duke) of Solms-Hohensolms—who ruled the area in which the Hauß family lived—a "cousin" of Queen Mary, and their relationship would eventually secure our ancestor's emigration to the New World.

And so on that lucky (if unfortunately incestuous) note, we meet our first known ancestor:

CHAPTER ONE: JOHANN CHRISTIAN HAUSS,

1666 - 1725. Johann Christian Hauss is born into a poverty-ridden, war-torn, plague-inflicted wasteland... and aren't we lucky for it!

LITERARY

SOURCES FOR THIS PAGE: